Author(s): Priyotisha Debroy and Prof. (Dr.) Bijayananda Behera

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 4

Citation: IJLSSS 3(4) 13

Page No: 131 – 144

ABSTRACT

The concept of surrogacy can be taken as an ‘arrangement’ wherein a woman gives her consent to bring into life a child with the assistance of assisted reproductive technology. In such terms of pregnancy, neither of the gametes belongs either to her or to her husband. She carries the child to full-term pregnancy with the intention to hand over the child to the intended couple, on whose behalf she holds the baby.

At present, the surrogacy regulation Act, 2021, aims to regulate the surrogacy practice by prohibiting commercial surrogacy and allowing only altruistic surrogacy by permitting medical expenses and insurance, only for Indian infertile couples. Therefore, how surrogacy is being practiced in India is one of the needs of ampere-hour discussion. Below given are the objectives of this paper;

- To know the socio-economic & legal statuses of surrogate mothers after the law has existed and come into effect.

- To critically examine the present surrogacy law from the perspective of the surrogate mother.

The methodology opted for in this study is doctrinal and empirical. The researcher analyzed the data collected through an empirical study in the Anand district of state of Gujarat with simple statistical tools to verify the stated objectives. The researcher found that surrogate mother’s socio-economic status is compromised after the enactment and enforcement of present surrogacy law. The researcher concludes that the present surrogacy law needs to be amended for the protection of surrogate mother for the exploitation and baby black market in India.

Key Words: Altruistic Surrogacy, Commercial Surrogacy, Exploitation, and Reproductive Technology

INTRODUCTION

The practice of surrogacy—wherein a woman consents to carry and give birth to a child on behalf of another individual or couple—has sparked considerable debate in India. Initially a relatively obscure concept, surrogacy began gaining widespread attention with the advent and advancement of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART). By the early 2000s, India had emerged as a global hub for commercial surrogacy, largely due to its cost-effectiveness and the absence of a stringent regulatory regime. The comparatively lower cost of medical procedures, coupled with permissive legal norms at the time, made India an attractive destination for foreign couples seeking surrogacy arrangements. This led to the growth of what came to be known as the “surrogacy industry.[1]”

However, the rapid commercialization of surrogacy brought forth complex ethical, legal, and social challenges. Numerous cases of surrogate exploitation, inequitable contractual arrangements, and disputes over parenthood began to surface. These developments exposed the vulnerabilities of unregulated surrogacy and underscored the urgent need for comprehensive legal safeguards. In response to mounting criticism from both domestic and international observers, the Indian government initiated legislative reforms aimed at protecting the interests of surrogate mothers, intending parents, and children born through such arrangements. This culminated in the enactment of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021—a landmark legal reform that marked a shift in India’s surrogacy policy. The Act outlawed commercial surrogacy and permitted only altruistic surrogacy, thereby placing a stronger emphasis on ethical and non-commercial motivations behind surrogacy arrangements. The introduction of this legislation has significantly altered the legal landscape surrounding surrogacy in India. It has introduced new challenges concerning the enforceability of surrogacy agreements and raised critical questions regarding the rights and responsibilities of all involved parties[2].

To navigate the complexities of surrogacy law, it is important to understand the core concepts and terminology. Surrogacy is fundamentally a contractual arrangement where a woman, known as the surrogate, agrees to become pregnant and deliver a child for another person or couple—referred to as the intending or commissioning parents—who plan to assume legal parenthood following the child’s birth. Surrogacy may take two primary forms: gestational and traditional. In gestational surrogacy, the child is conceived via in vitro fertilization (IVF) using the genetic material of the intended parents or donors, and the surrogate has no biological link to the child. In contrast, traditional surrogacy involves the surrogate’s own egg, making her the biological mother of the child. A surrogacy agreement is a legal contract that outlines the specific terms and responsibilities of both the surrogate and the intending parents. This may include clauses concerning medical care, responsibilities during the pregnancy, and in cases where commercial surrogacy was once legal, details about compensation. The objective of such agreements is to ensure legal clarity and protect the interests of all parties by reducing the potential for future disputes. The surrogate mother is the woman who voluntarily carries a child for the intended parents. In altruistic surrogacy—now the only legally sanctioned form in India—she does not receive any financial compensation beyond reimbursement of medical and pregnancy-related expenses. This stands in contrast to the formerly permitted model of commercial surrogacy, in which the surrogate would be paid for her services. Intending parents are individuals or couples who engage a surrogate to bear a child on their behalf. Upon the child’s birth, they assume full legal parenthood, along with the associated rights and responsibilities, as defined by the surrogacy agreement and existing legal provisions[3].

Motherhood is often regarded as a natural and cherished blessing bestowed upon women, symbolizing growth, nurturing, and selfless love from the moment of conception through the various stages of a child’s development. Throughout her life, a woman may take on multiple roles, with motherhood being one of the most significant. It is commonly perceived in many cultures that motherhood completes a woman’s identity. However, not all women are able to experience motherhood through natural means due to health-related challenges such as infertility—a condition that affects individuals globally.

The advent of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) has significantly transformed the field of reproductive health, offering new avenues for individuals and couples to have genetically related children. Surrogacy, as a form of assisted reproduction, has historical roots that date back to ancient scriptures such as the Bible and Hindu Puranas, indicating that infertility has long been a concern for humanity. Infertility can be attributed to male factors, female factors, or a combination of both, and it is broadly classified into two categories: primary infertility, which refers to the inability to conceive a child, and secondary infertility, which denotes the inability to conceive following a previous successful pregnancy. In India, infertility is reported to affect approximately 10–15% of the population.

Indian society places immense value on marriage, family, and procreation. Consequently, couples facing infertility often experience considerable pressure and emotional distress stemming from societal expectations, family structures, and entrenched gender norms. The inability to bear children is frequently viewed as a deviation from social conventions, and women, in particular, may be subjected to stigma and emotional marginalization, as motherhood is frequently considered a vital aspect of womanhood and femininity. Additionally, due to a strong cultural emphasis on preserving biological lineage and maintaining a “pure bloodline,” many Indian couples tend to prefer surrogacy over adoption.

Technological advancements, particularly the development of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), have revolutionized reproductive healthcare by enabling individuals and couples to conceive genetically related offspring. Surrogacy has emerged as a vital component of assisted reproductive technologies, offering an alternative route to parenthood for those unable to conceive naturally. Notably, the concept of surrogacy is not new—it has been referenced in ancient religious texts such as the Bible and Hindu Puranas, highlighting that infertility has long been recognized as a human struggle. Medically, infertility may arise from male factors, female factors, or a combination of both. It is commonly categorized into two types: primary infertility, which is the inability to achieve pregnancy, and secondary infertility, which refers to the failure to conceive again after a previous successful pregnancy. In India, infertility affects an estimated 10–15% of the population, reflecting a growing public health issue[4].

In Indian culture, there is profound social importance placed on marriage, childbearing, and family life. As a result, couples dealing with infertility often encounter intense societal pressure and emotional turmoil. These experiences are shaped by entrenched expectations surrounding family roles and gender norms. In particular, women who are unable to conceive may face social stigma and emotional isolation, as motherhood is frequently perceived as an essential component of feminine identity. Furthermore, due to the cultural priority placed on continuing one’s biological lineage and preserving what is often referred to as a “pure bloodline,” surrogacy is frequently favoured over adoption among Indian couples[5].

Conducting an in-depth examination of the Surrogacy Regulation Act is crucial for dispelling widespread myths and misconceptions surrounding the practice. Surrogacy is often unjustly equated with prostitution, and this study aims to challenge such stigmatized views by highlighting the positive and transformative dimensions of surrogacy.

Furthermore, surrogacy continues to be a subject of complex social, legal, and ethical debate globally. While it is legally recognized and regulated in several countries, it remains a controversial and stigmatized issue in others. This study also offers a comparative perspective by exploring the diverse legal frameworks governing surrogacy across different regions of the world.

This research paper explores the experiences and perspectives of surrogate mothers who had previously participated in surrogacy arrangements prior to the enactment of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021. The researcher conducted fieldwork in Anand, Gujarat—an established hub for surrogacy—engaging with 25 surrogate mothers as well as Dr. Nayana Patel, a renowned fertility specialist with over three decades of experience in the field. The study aims to assess the impact of the 2021 legislation on these women and to understand their views on the prohibition of commercial surrogacy. The research investigates whether the surrogate mothers support the government’s decision to ban commercial surrogacy or if they express discontent with the policy, shedding light on the socio-economic and emotional implications of the legislative shift[6].

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021, currently governs surrogacy practices in India by prohibiting commercial surrogacy and permitting only altruistic surrogacy. Under this framework, only Indian infertile couples are eligible, and the surrogate is entitled solely to reimbursement of medical expenses and insurance coverage. Given the significant transformation in the legal and ethical landscape surrounding surrogacy, it is imperative to critically examine how surrogacy is being practiced in India today. This paper seeks to address the following key objectives:

- To examine the socio-economic and legal conditions of surrogate mothers in the post-legislative context following the enactment of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

- To undertake a critical evaluation of the current surrogacy legislation from the viewpoint of surrogate mothers, with a focus on its implications for their rights, agency, and well-being.

METHODOLOGY

The methodology opted for in this study is doctrinal and empirical, with snowball sampling. The researcher analyzed the data collected through an empirical study in the Anand district of state of Gujarat with simple percentages and average statistical tools to verify the stated objectives.

And the traditional Doctrinal research method is used for referring from the articles, Books, journals and websites.

FEW LITERATURE REVIEW

- Chandrika Vishwakarma, Agony Of A Rented Mother: Who Were Actually Responsible For The Failure Of Commercial Surrogacy In India? , Journal on Contemporary Issues of Law Volume 3 Issue 8[7]: The Journal here has main focused on commercial surrogacy and why the Indian legal system has banned it completely without regulating it or going deep into the issue that if banned then what will be the economic impact of the poor women’s. The author has critically examined the surrogacy regulation bill 2016. The researcher had gone through the ground level problems and issues of surrogacy mothers which are occurring due to banning of commercial surrogacy. The critical analysis of the bill was done with a reason to every point she has stated. She has also given solid solutions to the proposed lacking of the bill. She wanted the Government and the law to make a legislation which will be surrogate mother centric not the intended couple centric. There is a question if the law would have been regulated the surrogacy, would it have been so exploitative towards surrogate mothers? By banning commercial surrogacy it will not only make poor women’s more vulnerable also it will rise more illegally. Her reason is that in country of poverty and unemployment it should regulate the commercial surrogacy with proper backup and whosoever try to exploit or make use of the mothers out of this process should be penalized.

- Diksha Munjal-Shankar, Commercial Surrogacy in India: Vulnerability Contextualized: Journal of the Indian Law Institute, Vol. 58, and No. 3 (July – September 2016)[8]: The Journal mainly focuses on the vulnerability of the surrogate mothers. She has given a reference of an empirical study which had been held by some other researcher that the surrogate mothers were being exploited as they were illiterate. They couldn’t even read the agreements which were being signed by them and they had pure trust o the Doctors of the clinics. In that study it was seen that surrogate mothers were being kept in a hostel like ward where they were not allowed to visit their homes. They were being fed and other precautions were being taken by the clinics. The surrogacy industry were blooming at that time without any adequate legal binding and the researcher attempts to delve into various aspects of vulnerability of surrogate mother and the children born out of the surrogacy. She explains the concept of vulnerability in her paper and also she engages vulnerability with responsibility in one of her chapters. Thus it’s a paper critically examining the commercial surrogacy within India.

- Kolhe, S., Gupta, K., & Gupta, A. (N.D.). Commercial Surrogacy: A Cluster Of Issues And Complexities Of Rights Under The Constitution Of India, Vol. IX, Issue II, 422-467[9]– as the name presented in the title of the article, the author discussed the complexities and issues surrounding commercial surrogacy in India. The paper argues that in light of the bill Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019 fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, violates it. The document argued that constitutional analysis in contrary to the Bill. The Bill violated Article 14, 19 and 21 which is right to equality, freedom of trade and commerce and right to life and personal liberty of the Constitution. The paper talked about the bill’s restrictions on who can avail surrogacy which lacked rational basis. The banning of the commercial surrogacy also infringes the rights of the surrogate mother’s right to livelihood and the intended parent’s reproductive autonomy. The paper discusses various international commercial surrogacy laws in different countries, like Israel, Ukraine and some other states in the USA. Because there commercial surrogacy is legal and being regulated. It also discusses reproductive rights and supports it through the article. The other side of the article is that, the author presented a different perspective on commercial surrogacy. the author said that patriarchal mentality oppose the surrogacy as an arrangement that view motherhood as a women’s prerogative which she should do by following altruism. This view is challenged by the author who suggests that surrogacy should be of gestational in behaviour. Women should be fairly compensated for the gestational service. There is a changing nature of the morality here. Because there’s a recent decriminalization of homosexuality in India and also accepting surrogacy. The author proposed many suggestions for regulating commercial surrogacy in this article at the end.

- Chang, Mina, Womb for Rent: India’s Commercial Surrogacy. Harvard International Review, 2009- The researcher here has analyzed that in India from a marginalized society it has become a blooming industry after commercial surrogacy were legalized since 2002. Thus it has fueled concern that it could be just another form of exploitation of race, gender and class. It is being referred as cheap commodity. The researcher with main focus to the ethics in Indian culture has questioned that is commercial surrogacy is a oppression or opportunity? She stated that in the highest mortality rate in terms o pregnancy it the law should protect the surrogate mothers and give adequate policy so that it could balance both the side of surrogacy.

- Laura Harrison, Brown Bodies, White Babies: The Politics of Cross-Racial Surrogacy, (2016)- The book highlights the ways in which reproductive technologies, including surrogacy, are primarily used to reinforce the reproduction of the white, heterosexual, married, middle-class family. It also notes that the role of the surrogate is minimized when DNA is framed as the sole arbiter of the “true self.The study finds that cross-racial gestational surrogacy and reproductive tourism reflect and promote a popular understanding of distinct biological races, despite scientific debates.The key findings of the study include the defeat of personhood initiatives in Mississippi and other states, the concerns about limiting access to in vitro fertilization (IVF), and the potential implications for women’s health and reproductive rights. The article highlights how fetal personhood laws are used to restrict women’s reproductive autonomy, particularly for women of color, and how they intersect with issues of reproductive technologies, racial justice, and women’s health. It also notes that the pro-life movement’s focus on fetal personhood is often at the expense of women’s health and well-being. The objectives of the study are to analyze the discourse surrounding gestational surrogacy, examine the ways identity categories intersect to form nexuses of privilege and oppression, and contribute to the literature on reproductive technologies. The study employs a multisided, qualitative analysis of sources, including the law, mass media, the history of radicalized reproductive labor, and contemporary mediated spaces such as websites and databases. The methodology is interdisciplinary, allowing for themes to emerge after data collection. The study uses a qualitative approach, analyzing databases of egg donors and surrogates created by agencies, as well as secondary sources, magazine, newspaper, and television coverage, and documentary films. The book concludes that the contemporary attacks on women’s reproductive autonomy suggest the challenges that we continue to face, and that the potential for ARTs to complicate traditional notions of kinship, gender, and race is very real. The study concludes that reproductive tourism happens not only transnationally but also within national borders, and that the arguments and theoretical frameworks that underpin this research remain relevant. The article concludes that fetal personhood laws are a threat to women’s reproductive autonomy and that they intersect with issues of reproductive technologies, racial justice, and women’s health. It also notes that the pro-life movement’s focus on fetal personhood is often at the expense of women’s health and well-being.

THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS OF SURROGATE WOMAN: FIELD STUDY

ANALYSIS OF FIELD RESPONDENTS

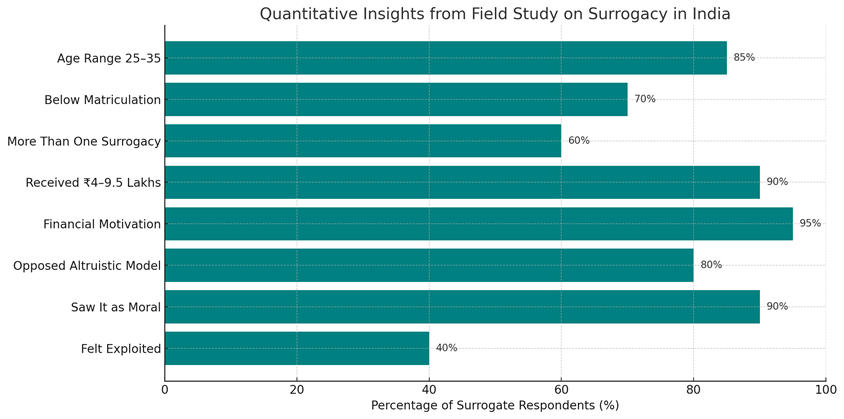

This section presents a quantitative summary of trends observed from the field interviews conducted with 20 surrogate mothers across Anand. While the study is primarily qualitative in nature, simple statistical tools were being used for the analysis.

AGE AND DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

A majority (85%) of the surrogate mothers were within the age bracket of 25 to 35 years, a finding consistent with medical guidelines on optimal reproductive age. This suggests a conscious selection either by clinics or surrogates themselves to maximize the chances of a successful pregnancy and reduce complications.

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Approximately 70% of the respondents had not completed matriculation, with only a few having completed higher secondary or college education. Despite this, their awareness of medical procedures, risks, and legal nuances was notably high—a result of structured counselling and repeated experience with clinics. This highlights a paradox: low formal education coexists with high procedural literacy in the surrogacy space.

REPEATED PARTICIPATION IN SURROGACY

Nearly 60% of surrogate mothers had opted to become surrogates more than once, with some having completed up to three surrogacies. Repeat participation was strongly tied to financial need and perceived safety of the clinical environment, indicating trust in the process and economic dependence on surrogacy income.

COMPENSATION RECEIVED

An overwhelming 90% of respondents received monetary compensation ranging from ₹4 lakhs to ₹9.5 lakhs, depending on factors such as location, number of foetuses, and hospital policies. The compensation was often described as life-changing, enabling investments in housing, children’s education, debt repayment, or small business ventures.

PRIMARY MOTIVATION: FINANCIAL DISTRESS

95% of surrogate mothers cited financial constraints as the primary motivator for entering into surrogacy. Many respondents were single, widowed, or came from families living below the poverty line. The practice was widely seen as a form of livelihood rather than exploitation—a conscious, informed decision made within constrained economic circumstances.

ATTITUDES TOWARD ALTRUISTIC SURROGACY

A striking 80% of respondents expressed disagreement with the current altruistic surrogacy model, stating that it fails to recognize the labour, risk, and emotional burden involved. Many viewed the 2021 Surrogacy Regulation Act as denying fair compensation to women who are already socio-economically vulnerable.

PERCEPTION OF MORALITY AND SOCIAL STANDING

90% of surrogate mothers did not view their participation in surrogacy as immoral or unethical. Instead, they expressed pride in being able to help childless couples and spoke of their role in moral, religious, and humanitarian terms. The work was often equated with performing a social good or punya (meritorious deed).

EXPLOITATION AND VULNERABILITY

Despite overall positive narratives, 40% reported feeling exploited, primarily due to the involvement of middlemen, agents, or coercive family members. A small number reported poor treatment in clinics or pressures to sign contracts they did not fully understand. However, many emphasized that exploitation stemmed more from third-party actors than from the surrogacy process itself.

CONCLUSION

This data affirms the necessity of nuanced policy that balances protection with agency. Banning commercial surrogacy without offering secure, regulated alternatives risks pushing the practice underground, thereby exacerbating the very exploitation it sought to prevent. The field data illustrates that surrogacy, when properly regulated, is seen by participants as a legitimate and empowering choice rather than a form of reproductive coercion.

THE FINAL FIGURE OF THE WHOLE STUDY

The chart titled “Quantitative Insights from Field Study on Surrogacy in India” below presents a consolidated view of trends observed among surrogate mothers interviewed during the field research. It reveals that a substantial majority (85%) of the respondents were aged between 25 to 35 years, aligning with medical recommendations for safe pregnancies. Around 70% had not completed matriculation, indicating low formal education but high procedural awareness due to clinical counselling. Financial need emerged as the dominant motivator, with 95% entering surrogacy for economic relief and 90% receiving compensation ranging between ₹4–9.5 lakhs, enabling many to make significant life improvements. Despite their socioeconomic vulnerability, 90% of the women viewed their role as moral and socially valuable, expressing pride in helping childless couples. However, 80% disapproved of the altruistic model under the 2021 Act, citing it as exploitative due to the absence of compensation. While most did not report coercion, 40% acknowledged feeling exploited—primarily by third-party agents or familial pressure. Overall, the data underscores the surrogate mothers’ preference for a regulated commercial model over an uncompensated altruistic framework.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS ON SURROGACY (REGULATION) ACT, 2021

Coming to the fact that the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act has been enacted with the thoughts and intention of regulating the surrogacy practice and combating exploitation of women and surrogates, however, the provisions that are being included in the Act are very discriminating towards women. There are concerns that women could be exploited in the newly formed Act instead of giving protection. The whole surrogacy industry might go as a black market due to high demand of the surrogate mother and for surrogate mother they are driven by the monetary compensation. There is nothing to provide extra protection to the surrogate mothers in that case. Rather than completely stopping the commercial surrogacy, if the policy would have made a protection and right based nature law for the surrogates, it would have been a better approach for all the parties involved in the surrogacy arrangement. In the succeeding paragraphs, the lacuna of the Act is –

- Women’s infringement of Reproductive rights

- Banning commercial surrogacy cannot solve the problem

- there is a discrimination against the children who are disabled

- the right to livelihood is being infringed

- the restricted definition of Intending couple/woman

- women’s exploitation getting higher

- for fixation of time limits in certain cases there is absence of provisions

- ambiguity in Provisions of the Act

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

In the field study that is being done in Anand, Gujarat with the surrogates was a eye opener that the present piece of legislation instead of protecting the surrogate, it gave concern to the women who were in this field or who wanted to become a surrogate. After the interaction with the surrogate mothers in different villages in the city of Anand, the researcher found out that the monetary compensation which the surrogates got after the delivery of the baby was actually so helpful to begin their livelihood in a different way. They could think of at least buying lands, saving the money for children’s education, buying a vehicle, building a house, using the money for medical purpose and renting some shops to use it for business and many more. The banning of the commercial surrogacy has hit hard to them. They cannot believe that more women who were willing to become surrogate now cannot become one. The wish getting fulfilled is the greatest joy that they have been experiencing with the monetary compensation from the intended parents. They used to stay in the surrogate hostel and through them the researcher got to know that that time was the best time in their life because they used to get food, medicines, fruits, everything necessary time to time in the hostel and didn’t have to work lie they do in the house even when they were pregnant with their own child. The surrogate mothers told that they were being taken care and used to get monthly allowance too including the foods, medicines and other things needed. Some surrogate told me that due to their alcoholic partner, Dr Nayana Patel ma’am even arranged a room to stay so that they can be safe. Moreover, nobody there forced them to become a surrogate mother. In fact there are counselling sessions so that everybody can understand the science based on surrogacy and not jump on it just because it is driven by money. The whole process of the surrogacy arrangement is being made understand so that they could also get educated on it and pass on the information even if someone miscommunicate or mislead them. All over the experience that is being shared by the surrogate are the real life stories and the present legislation did not protect their rights of livelihood of the surrogate mothers. The focus of the legislation to regulate the surrogacy without going on to the background of the surrogates with a complete stopping the commercial surrogacy will lead to more black marketing which is the main concern here. It may foster surrogacy exploitation and the underground black economy where surrogates and intended parents will be undertaking commercial surrogacy without being disclosed to any other. So in relation to the surrogacy arrangements in India, it is respectfully proposed that the Act should include some following clauses:

- Reproductive autonomy for both men and women.

- The new-born baby should be allowed to breastfeed through surrogate for six months. The child should now everything about his identity.

- The Act should abolish the distinction between impaired and able-bodies children

- To allow controlled commercial surrogacy so that the surrogates are not being exploited. And commercial surrogacy can only happen in Government hospitals.

- Unreasonable distinctions between married couples who are allowed to bear surrogates and others who are not. Because everybody has a equal right and violation of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution will not happen.

- The inclusion of third gender, single men, and live-in-partners should get the chance of surrogacy.

- The Acts provisions regarding the fixing of the time period, the concerned authorities, the need for surrogate counselling, the surrogates situation in the event of a postpartum delivery. The embryo transfer limit, the clarity of the entire surrogacy procedures expenses, and the surrogate’s anonymity must be clarified.

[1] India’s outsourcing starts in the womb. (2008, January 2). Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2008/01/indias-outsourc

[2] Macwan, P. (2021, June 30). A controversial ban on commercial surrogacy could leave women in India with even fewer choices. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/6075971/commercial-surrogacy-ban-india/

[3] Understanding India’s Surrogacy Regulation Act of 2021. (n.d.). Law For Everything. Retrieved from https://lawforeverything.com/surrogacy-regulation-act/

[4] Surrogacy in India. (2025, July). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surrogacy_in_India

[5] A critical analysis of Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021: key provisions and drawbacks. (n.d.). The Law Way With Lawyers Journal. Retrieved from https://www.thelawwaywithlawyers.com/a-critical-analysis-of-surrogacy-regulation-act-2021-key-provisions-and-drawbacks/

[6] A critical analysis of Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021: key provisions and drawbacks. (n.d.). The Law Way With Lawyers Journal. Retrieved from https://www.thelawwaywithlawyers.com/a-critical-analysis-of-surrogacy-regulation-act-2021-key-provisions-and-drawbacks/

[7] Vishwakarma, C. (n.d.). Agony of a rented mother: Who were actually responsible for the failure of commercial surrogacy in India? Journal on Contemporary Issues of Law, 3(8). Retrieved from https://jcil.lsyndicate.com/volume-3-issue-8/

[8] Munjal-Shankar, D. (2016). Commercial surrogacy in India: Vulnerability contextualized. Journal of the Indian Law Institute, 58(3), 313–334. Retrieved from https://www.jili.iil.edu.in/index.php/jili/article/view/…

[9] Kolhe, S., Gupta, K., & Gupta, A. (2023). Commercial surrogacy: A cluster of issues and complexities of rights under the Constitution of India. International Journal of Legal Developments and Allied Issues, 9(2), 422–467. Retrieved from https://ijldai.thelawbrigade.com/…