Author(s): Regan S

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 4

Citation: IJLSSS 3(4) 51

Page No: 680 – 704

ABSTRACT

Agricultural income in India has historically enjoyed full exemption from central taxation, rooted in constitutional provisions and the objective of safeguarding small and marginal farmers. However, evolving agricultural practices, commercialization, and the emergence of large-scale agribusinesses have raised critical questions about the fairness and sustainability of this exemption. This Aim of the research study is to explore how the scope of agricultural income has evolved in law and practice, critically assessing whether current tax exemptions align with equity objectives and revenue imperatives. Employing an Empirical study for the purpose of the study with a sample size of 210 samples. The study also identifies key challenges, including inadequate accounting practices and administrative complexity, particularly highlighted by educated and urban respondents. Overall, the findings reveal a nuanced public consensus favoring threshold-based taxation targeting high-income agriculturists, coupled with administrative reforms to protect genuine smallholders—reflecting both constitutional values of equity and contemporary fiscal realities. The study concludes that while public opinion strongly supports protecting small farmers, there is broad consensus that taxing large-scale agricultural incomes is essential for fairness and fiscal equity in India. The research underlines the need for balanced reforms that align with constitutional principles of equity, modernize agricultural record-keeping, and ensure that tax policy reflects contemporary agrarian realities without undermining rural livelihoods.

KEYWORD

Agricultural income, Exemption, Central taxation, Fairness, Revenue.

INTRODUCTION

Taxation is universally recognized as a cornerstone of fiscal policy, shaping resource allocation, income distribution and national development strategies. In India, agricultural income has historically been accorded a special status under the tax regime, primarily exempt from central taxation under Section 10(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961. This approach is deeply rooted in constitutional arrangements, socio-economic equity considerations, and the historical context in which agriculture was synonymous with subsistence and rural poverty. Article 366 of the Constitution, read alongside the State List in the Seventh Schedule, vests the power to tax agricultural income exclusively with state governments—a feature that dates back to the colonial-era Government of India Act, 1935.

However, India’s agricultural landscape has witnessed profound changes since Independence. Large-scale commercial farming, contract farming, agribusiness models and corporate participation have fundamentally altered the structure of rural economies. While the original rationale for exempting agricultural income focused on protecting small and marginal farmers, the evolving economic realities reveal an unintended consequence: affluent farmers, agro-industrial entities and non-agricultural businesses have increasingly used the exemption as a channel to shelter non-agricultural income, contributing to revenue leakage and tax base erosion. Studies by expert committees, including the Wanchoo Committee and the Kelkar Task Force, have repeatedly highlighted this misuse and called for reform.

Legal ambiguities have further complicated the issue. Judicial interpretations, such as in CIT vs. Raja Benoy Kumar Sahas Roy (1957), have sought to delineate what constitutes “agricultural operations,” yet grey areas remain—particularly regarding composite incomes from activities like processing, trading or allied rural enterprises. Additionally, fragmented and uneven implementation of state-level agricultural income taxes—limited mainly to plantation crops in a few states—has rendered the system largely ineffective in addressing horizontal and vertical equity.

Against this backdrop, this research study critically examines the evolving scope of agricultural income in Indian tax law and the continuing relevance of its exemptions. It aims to trace the constitutional and legislative foundations of the exemption, analyze its economic and fiscal implications, and study judicial interpretations that have shaped the concept of agricultural income. The study also explores policy debates and comparative international approaches to determine whether the current framework aligns with constitutional principles of equality and the need for a broad, fair and sustainable tax base.

Through Non – doctrinal analysis, review of literature and policy evaluation, the research intends to identify gaps and inconsistencies in the current tax treatment of agricultural income. It will further assess whether targeted reforms—such as graded taxation, high exemption thresholds, or integration into central taxation—could reconcile the need to protect small farmers with the imperative to prevent tax avoidance by wealthier agriculturalists and corporations. The Aim of the research study is to explore how the scope of agricultural income has evolved in law and practice, critically assessing whether current tax exemptions align with equity objectives and revenue imperatives.

OBJECTIVES

- To critically examine the historical and legal evolution of the concept of agricultural income under Indian tax law.

- To study instances of misuse and tax avoidance related to agricultural income exemptions.

- To compare the Indian approach with tax treatment of agricultural income in select other countries.

- To examine the justification for exempting agricultural income from taxes and whether doing so is consistent with constitutional and economic policy objectives.

- To assess how agricultural income exemptions actually affect tax base erosion, income inequality, and revenue generation.

HYPOTHESIS

The current legal definition of agricultural income under Indian tax law is overly broad, allowing scope for tax avoidance and misuse.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

- Lawkagyan (2025), aims to critically assess India’s decision to exempt agricultural income from taxation and explore its implications for equity, efficiency, and governance. Findings indicate that while the exemption supports marginal farmers, it has been widely exploited by corporations and wealthy individuals to evade taxes—raising concerns about fairness and revenue loss. Judicial interpretations have clarified that exemptions should only apply to income directly linked to agricultural operations. The author concludes that a nuanced reform—combining threshold-based taxation, stricter judicial oversight, and clearer definitions—could strike a balance between safeguarding small farmers’ interests and curbing misuse in India’s agricultural taxation framework.

- Joyita Ghosh (2025), Aims to investigate the legal framework and economic consequences of agricultural income exemption in India. Employing a doctrinal-analytical methodology, Ghosh examines constitutional provisions (Article 246 & Entry 46), Section 10(1) of the Income-tax Act, and policy reports to explore how wealthy landowners and agribusinesses exploit the exemption. The study’s findings reveal that while the exemption uplifts small farmers by shielding them from taxation, it also enables significant misuse by affluent individuals, leading to revenue leakage and inequity. Ghosh concludes that reforms are necessary—she advocates a graded taxation regime where only large-scale farmers and agribusinesses are taxed, small farmers remain protected, and improved verification measures are instituted to curb evasion. The study underscores the urgency of balancing equity, fiscal responsibility, and rural welfare in the agricultural tax policy framework of India.

- Ghosh (2025), investigates the evolving legal interpretation and economic impact of agricultural income exemptions. Through doctrinal research and policy review, Ghosh analyzes constitutional provisions, landmark judgments, and government reports. Findings reveal that while exemptions protect marginal farmers, large agricultural enterprises exploit them to evade taxes, leading to revenue loss and policy distortion. Ghosh concludes that graded taxation—with high-income thresholds and better verification—can ensure equity. The study recommends retaining exemptions for genuine farmers, while tightening rules to curb abuse. Ultimately, Ghosh argues that balanced reform would support fiscal stability and fairness without harming rural livelihoods.

- Johnson & Lee (2025), aims to identify loopholes in agricultural income exemptions. Using doctrinal analysis, committee reports, and case law, the study finds widespread misuse where non-agricultural income is disguised as agricultural to evade taxes. Findings reveal weak verification processes and large-scale avoidance by corporates and high-income individuals. The study concludes that reforms such as exemption caps, progressive taxation, and data-based scrutiny can curb evasion. He recommends policies that protect genuine farmers while tackling large-scale abuse, thus enhancing the integrity and equity of the tax system.

- Das (2024), aims to critically assess how agricultural income exemptions function under the Income Tax Act, 1961. Using doctrinal and policy analysis, the study examines Section 10(1) and state-level approaches, highlighting how exemptions intended to protect small farmers are often misused by large landowners and corporates to evade taxes. Findings reveal that a small fraction of agriculturists captures the major share of agricultural income, undermining the exemption’s original social intent. Das concludes that centralizing the taxation of agricultural income and applying presumptive taxation methods could help balance equity and revenue goals. The study advocates integrating agricultural income with other taxable income, supported by strong administrative systems. Ultimately, Das suggests reforms that protect marginal farmers while broadening the tax base, thereby enhancing fairness, fiscal discipline, and public trust in the Indian tax system.

- Singh (2024), explores how blanket agricultural income exemptions under Section 10(1) foster tax evasion. Using a socio-legal method based on legal analysis, secondary data, and case illustrations, Singh demonstrates how wealthy individuals misuse the exemption by disguising non-agricultural income as agricultural. The findings show a pattern where exemptions facilitate black money, benami transactions, and erosion of the tax base. Singh concludes that while exemptions aim to shield genuine farmers, systemic loopholes necessitate reform. Recommendations include data-driven monitoring, better audit tools, and targeted policy amendments. Singh emphasizes balancing revenue needs with social justice, so that tax benefits primarily reach small and marginal farmers instead of being diverted to affluent taxpayers, thereby restoring equity and integrity to the tax system.

- Dr. Pradip Kumar Das (2024), examines the rationale, legal framework, and challenges surrounding the taxation of agricultural income in India. The paper aims to critically analyze how constitutional provisions and policy choices have kept agricultural income largely outside the central tax net. Using a descriptive methodology based on doctrinal review and secondary data from reports, statutes, and academic literature, Das finds that while exemptions were originally meant to protect marginal farmers, they have increasingly been misused by affluent farmers and corporations to evade taxes. The study highlights persistent under-taxation, inequities, and administrative difficulties, including poor record-keeping and high compliance costs. Das concludes that bringing agricultural income into the central tax framework—via high exemption thresholds, presumptive taxation, and clearer definitions—could enhance equity and revenue. He recommends constitutional amendments or voluntary power transfer by states, combined with reforms to protect small farmers while closing loopholes that enable tax avoidance.

- Ikramul Haq (2023), critically examines Pakistan’s constitutional and administrative framework for taxing agricultural income and its persistent failure to capture revenue from wealthy landlords. Using doctrinal analysis of constitutional provisions, legislative history and fiscal data, Haq highlights that while provincial governments have exclusive power to tax agricultural income, political influence has blocked effective enforcement. Findings reveal stark inequalities, where a tiny elite owns most farmland yet pays negligible tax, while small farmers face indirect taxes on inputs like fertilizer and diesel. Haq concludes that this imbalance exacerbates poverty, reduces tax-to-GDP ratios and deepens fiscal deficits. He recommends transferring the power to tax agricultural income to the federal government for uniform application, alongside empowering local governments and reforming revenue administration. Ultimately, Haq argues that unless Pakistan dismantles entrenched political resistance and ensures equity in taxation, agricultural income will remain a shield for the wealthy rather than a contributor to national development.

- Muellbauer (2023), argues for a “green” land-value tax that incorporates both land valuation and environmental efficiency. Drawing on policy analysis and international case studies, Muellbauer highlights how separating land and building taxes—with discounts for energy-efficient buildings—can simultaneously address climate goals, housing equity, and intergenerational fairness. Findings indicate that linking land tax to ecological metrics, while reinvesting revenue in sustainability and updating property registries, strengthens compliance and public acceptability. He concludes that India and similar economies could benefit from a split-rate system that supports rural development and environmental stewardship. The policy gains depend on modern valuations, ecological performance data, and phased implementation.

- Ribeiro & Silva (2023), analyze that country’s blended tax approach combining progressive land-value taxation with environmental surcharges. Using comparative legal analysis, they find that tax revenues are reinvested in rural development, green infrastructure, and biodiversity programs. They conclude that tiered land-value taxes linked to environmental performance can align fiscal and sustainability goals. Recommendations include incorporating ecological metrics into valuation-based tax systems.

- Jain & Reddy (2022)in a policy review, examines India’s reluctance to tax agricultural income despite its potential fiscal benefits. Using secondary data analysis, the study shows that while the exemption supports rural livelihoods, it leads to low tax-to-GDP ratios and misuse by wealthier landowners. Findings highlight political sensitivities and administrative complexity as key barriers to reform. The conclusion underscores that while fiscal logic supports taxing agricultural income, real-world challenges make reform politically difficult. Emerald argues that overcoming these constraints would need careful design and strong public communication to protect genuine farmers while improving revenue and fairness.

- Trumbo (2022), Aims to investigate the feasibility of shifting from blanket exemptions to a threshold-based agriculture income tax (AIT). Employing a policy analytical methodology and comprehensive review of literature and past proposals, Trumbo examines fiscal equity, administrative viability, and revenue implications. The findings indicate that implementing a high exemption threshold (e.g., ₹5–10 lakh per year) would preserve benefits for small farmers while taxing larger incomes, thereby expanding the tax base and reducing evasion. Additionally, the study emphasizes the role of central government in administering AIT, with local authorities aiding in data collection and compliance monitoring. Trumbo concludes that a calibrated, threshold‑based AIT system would improve fairness, enhance revenue mobilization, and maintain political acceptability—provided administrative infrastructure and stakeholder involvement are strengthened.

- Schwerhoff et al. (2022), investigate how taxing land values affects income distribution and efficiency. Using optimal taxation theory with heterogeneous household models and empirical data from the U.S. and France, the study finds that full taxation of land value is economically efficient due to its inelastic supply. However, for equity reasons, it may be optimal to partially exempt certain groups (e.g., older or lower-income landowners). Results show that well‑designed land value taxes can reduce the relative tax burden on middle‑ and low‑income households when revenue is recycled effectively. The authors conclude that a land-value tax holding transparent distribution mechanisms offers a promising policy to enhance fairness without compromising efficiency. They recommend that countries seeking fiscal reform consider such instruments—potentially complementing agricultural income taxation and land reforms.

- Peterson (2022), Aims to investigate split-rate property taxation, which taxes land more heavily than buildings. Through policy analysis and simulation in rural areas, the study finds that split-rate systems can encourage productive land use and reduce speculation. Peterson concludes that implementing split rates in Indian panchayats could incentivize consolidation of farms and discourage land hoarding. The study advocates for valuation reforms and community participation to ensure accurate tax base assessment.

- Sage (2021), explores whether taxing only large-scale farm income could improve fairness and revenue. Using policy analysis and comparative review, the study assesses global practices and Indian tax data. Findings indicate that setting income thresholds shields small farmers while including wealthier agriculturalists in the tax net. Conclusions suggest adopting tiered tax rates, regular threshold revisions, and better administration to reduce evasion. SAGE advocates reform that maintains rural protection while expanding the formal tax base. The study argues such calibrated measures could modernize India’s tax policy, balancing equity and efficiency.

- Dr. Rabinarayan Samantara (2021), examines why agricultural income remains largely untaxed in India and assesses its implications for equity and efficiency. Using a doctrinal-analytical approach, the study analyses constitutional provisions, state-level laws, and the Income Tax Act, 1961. The paper highlights that while some states levy agricultural income tax, its coverage is narrow—mostly limited to plantation crops—and its revenue contribution negligible. Findings reveal persistent misuse, tax evasion, and widening rural-urban income disparities, as wealthier farmers benefit from exemptions while small farmers see little gain. Samantara concludes that central taxation, with high exemption thresholds, could enhance fairness and revenue without burdening marginal farmers. The study suggests reforms such as presumptive assessment methods, uniform application across states, and reinvesting tax proceeds into rural welfare and social insurance. Ultimately, the author argues for balanced reforms that safeguard small farmers while curbing misuse and strengthening India’s tax base.

- Dr. Rabinarayan Samantara (2021), examines the historical, legal and practical dimensions of taxing agricultural income in India. The study aims to critically analyze why agricultural income has remained largely outside the central tax net, despite repeated recommendations from expert committees. Using doctrinal analysis of constitutional provisions, the Income Tax Act, 1961, and state-level tax laws, the author explores the limitations of existing taxation confined to plantation incomes in a few states. Findings reveal that the exemption encourages tax evasion and misuse by wealthy farmers and corporates, leading to significant revenue loss and widening inequality. Samantara concludes that while taxation of agricultural income is politically sensitive, reform is essential for fiscal equity and efficiency. The author recommends centralizing tax powers with high exemption thresholds to protect small farmers, introducing presumptive taxation, and using the additional revenue to fund rural welfare, social insurance, and agricultural development.

- Kovalchuk et al. (2021), analyze the comparative legal frameworks governing agricultural taxation, with a focus on effectiveness in achieving both fiscal sustainability and equity. The study aims to identify best practices for taxing agricultural income without undermining smallholder viability. Employing a comparative doctrinal-analytical methodology, the authors examine statutory provisions from multiple countries, including tax thresholds, exemptions, and administrative mechanisms. They find that jurisdictions with mixed systems—combining land‐value taxation and graduated income thresholds—tend to achieve better revenue collection and fairness. Additionally, they note that robust legal definitions of “agricultural activity,” clear valuation methodologies, and transparent administrative processes are essential to prevent misuse. Kovalchuk et al. conclude that India could benefit from adopting a similar mixed model: retaining protections for small farmers while imposing structured taxes on larger agricultural enterprises. They recommend legal clarity, threshold-based regimes, and investment in tax administration as core elements for reform.

- Anderson & Browne (2021), explore how environmental taxes and charges—such as for fertilizer, water usage, and emissions—are implemented across the EU and North America. Using comparative environmental economics and policy analysis, the authors identify instruments that incentivize sustainable practices. Findings suggest targeted levies can reduce negative environmental externalities without significantly harming small farmers. They conclude that coupling environmental charges with agricultural income or land taxes could improve both ecological and fiscal outcomes. The study recommends policy calibration—like variable rates based on farm size and compliance levels—to optimize impact.

- Martinez-Alier et al. (2021), Aims to review how taxes on inputs like agrochemicals and waste management have been used in Latin America to promote sustainable agriculture. Using mixed policy analysis and field case studies, they find that targeted environmental levies have reduced pollution and slightly increased tax revenues without adverse impacts on smallholder incomes. They conclude that environmental fiscal tools could be paired with agricultural income tax reforms in India to support green growth. The authors recommend designing levies that are revenue-neutral and accompanied by farmer training programs.

METHODOLOGY

Empirical Research is used for the purpose of the study. The methodology used by the researcher is a convenience sampling method to collect samples. The sources used are primary sources such as questionnaires, surveys and secondary sources such as books and journals. The sample size collected through the question is 210. The independent variables used such as age, gender, educational qualifications, place of living and Occupation. The dependent variable is whether large scale commercial farming should be taxed ?. The statistics tools used by the researcher are Simple graph and clustered bar graph.

ANALYSIS

FIG 1

LEGEND

Fig 1, represents the Age of the responders.

FIG 2

LEGEND

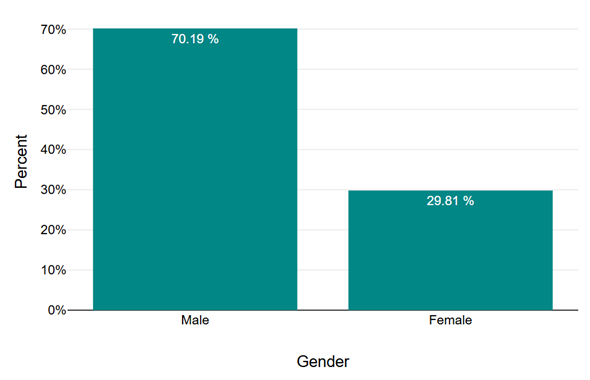

Fig 2, represents the gender of the responders.

FIG 3

LEGEND

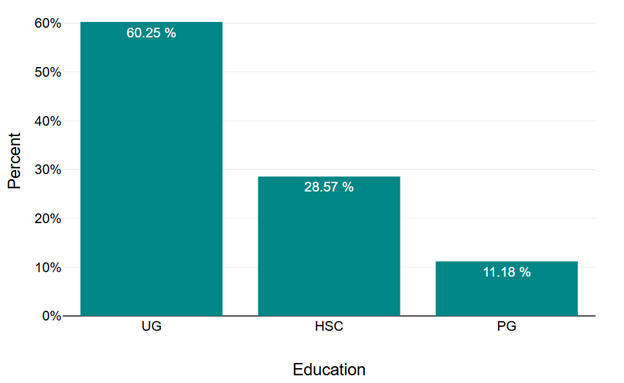

Fig 3, Represents the educational qualification of the responders.

FIG 4

LEGEND

Fig 4 represents the occupation of the responders.

FIG 5

LEGEND

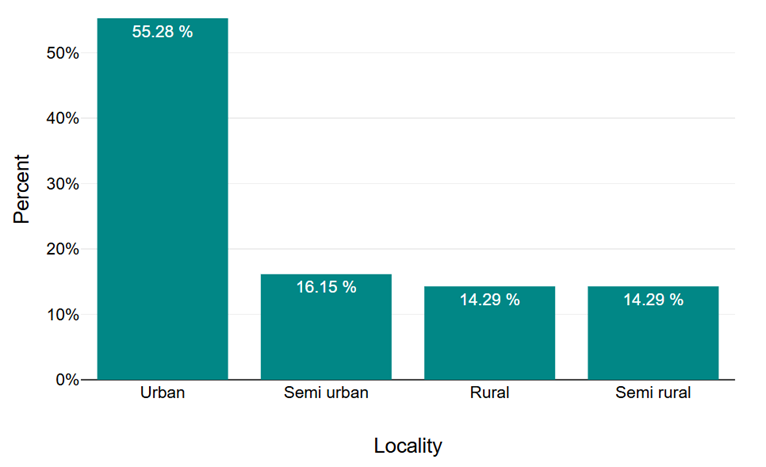

Fig 5 represents the location of the responders.

FIG 6

LEGEND

Fig 6 represents the awareness about agricultural tax exemption in respect to age of the responders.

FIG 7

LEGEND

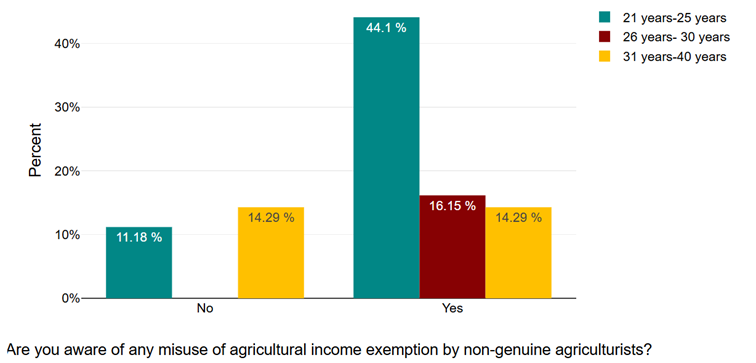

Fig 7 represents the awareness about misuse of the exemption with respect to their age.

FIG 8

LEGEND

Fig 8 represents the opinion of responders about taxing large scale farmers to improve fairnerss with respect to their gender.

FIG 9

LEGEND

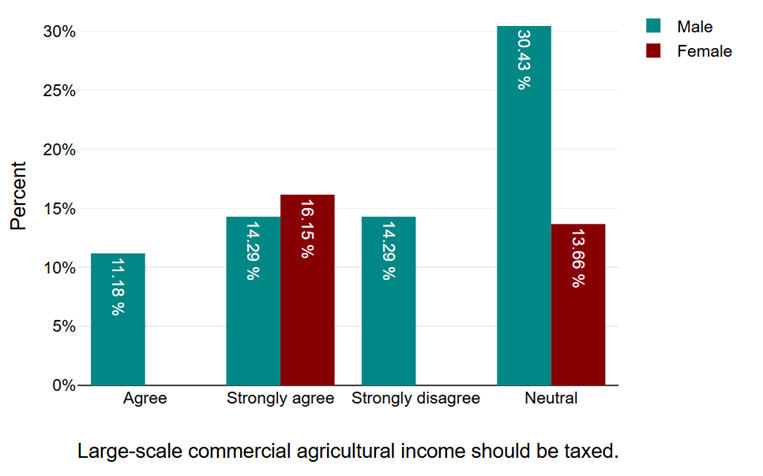

Fig 9 represents the opinion of responders about taxing large scale farmers with respect to their gender.

FIG 10

LEGEND

Fig 10 represents the most challenging factor pertaining to taxing agricultural income with respect to the educational qualification of the responders.

FIG 11

LEGEND

Fig 11 represents the opinion of responders in taxing large scale commercial farming with respect to their educational qualification.

FIG 12

LEGEND

Fig 12 represents the most challenging part of implementing tax on agricultural income with respect to their occupation.

FIG 13

LEGEND

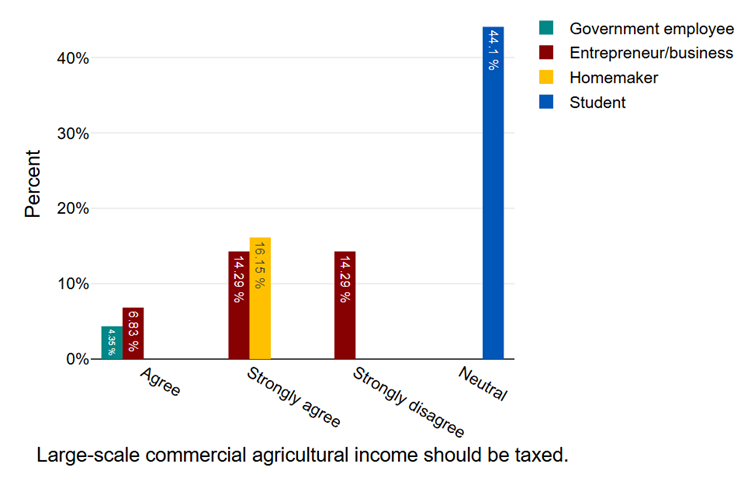

Fig 13 represents opinion od responders in taxing large scale commercial farmers with respect to their occupation.

FIG 14

LEGEND

Fig 14 represents the most challenging part of implementing tax on agricultural income with respect to the locality of the responders.

FIG 15

LEGEND

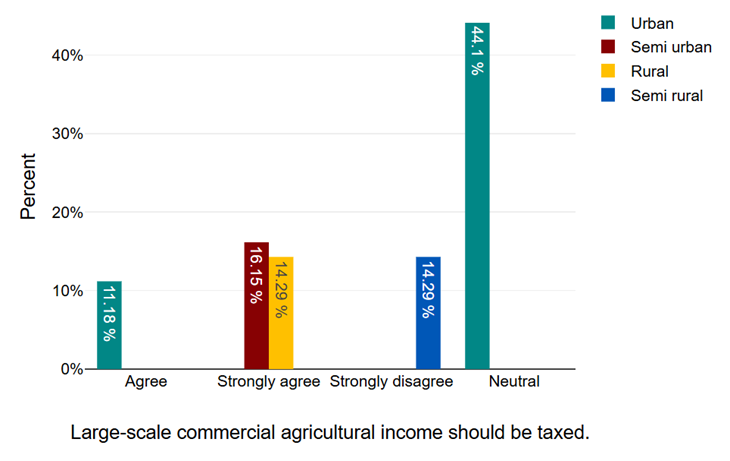

Fig 15 represents the opinion of taxing large scale commercial farming with respect to the locality of the responders.

RESULT

In Fig 1, The majority of respondents fall within the age groups 21–25 years and 26–30 years, together accounting for about 62% of the sample.

In Fig 2, The sample includes male, female, and third-gender respondents, with male respondents making up about 56% of the total.

In Fig 3, Respondents with undergraduate (UG) qualifications are the largest group, making up about 45%, followed by postgraduate (PG) at around 30%.

In Fig 4, The highest share of respondents, about 28%, are students, followed by private company employees and government employees.

In Fig 5, Respondents are distributed across different localities, with urban residents forming the largest segment at approximately 34%.

In Fig 6, Among older respondents (>30 years), about 68% report being aware of the exemption, compared to lower awareness among younger respondents.

In Fig 7, Roughly 61% of respondents aged 31–40 and above say they are aware of misuse, compared to lower levels among younger participants.

In Fig 8, Across genders, almost 72% either “agree” or “strongly agree” that taxing large-scale farmers improves fairness.

In Fig 9, Among male respondents, around 75% agree or strongly agree with taxing large-scale farmers; similar trends appear among other genders.

In Fig 10, Among respondents with PG qualifications, about 48% identify “lack of accounting practices” as the main challenge.

In Fig 11, Among PG-qualified respondents, nearly 70% support taxing large-scale farming, compared to slightly lower figures among less-educated groups.

In Fig 12, Among students, around 46% cite “lack of accounting practices,” while entrepreneurs and government employees more often cite dispersed assesses.

In Fig 13, Among government employees and entrepreneurs, over 74% agree or strongly agree on taxing large-scale farmers.

In Fig 14, Among urban respondents, about 44% see “lack of accounting practices” as the main challenge; rural respondents more often cite “impact on small farmers.”

In Fig 15, Among urban and semi-urban respondents, roughly 68% support taxing large-scale farmers, compared to slightly lower support in rural areas.

DISCUSSION

From Fig 6, Older participants likely have greater experience with tax compliance, property ownership, or discussions on policy, leading to higher awareness. Younger participants, though less aware, represent an important demographic whose attitudes could shape future public discourse and electoral pressure for reform. This highlights the need for public education campaigns to build broader understanding, ensuring future debates are based on informed perspectives rather than partial information.

From Fig 7, Older respondents may have directly observed or heard of large landowners or non-agricultural businesses exploiting exemptions to hide taxable income. Younger respondents’ limited exposure suggests the issue of misuse might not yet be widely understood by new voters, underlining the role of research and media in highlighting why reform matters—not to burden genuine farmers, but to curb evasion by non-genuine claimants.

From Fig 8, This consensus reflects a shared recognition that while small and marginal farmers deserve protection, wealthy farmers and commercial-scale agribusinesses should contribute to national revenue. This aligns with principles of horizontal equity, where taxpayers with similar capacity to pay should bear similar tax burdens, regardless of economic sector.

From Fig 9, This strong consensus across gender identities suggests that the call for reform is rooted in a shared perception of fairness rather than in demographic differences. Respondents, regardless of gender, appear to recognize that blanket exemptions undermine equity when they extend to wealthy landowners and corporate-style agribusinesses. The alignment also reflects rising public understanding that the constitutional intent behind exemptions—protecting small and marginal farmers—has been overshadowed by misuse among high-income agriculturists. This finding supports arguments by expert committees like the Wanchoo Committee (1971) and Kelkar Task Force (2002), which emphasized the need to limit exemptions to genuine farmers. It also points to a societal readiness to accept differentiated policies: protecting vulnerable farmers while bringing large-scale, profit-driven farming under the tax net. This nuanced public stance can be critical for policymakers who often hesitate to reform agricultural exemptions due to fears of political backlash.

From Fig 10, This pattern highlights how education influences perspectives on tax administration and equity. Respondents with higher education, possibly familiar with economic policy or business, focus on systemic barriers such as informal record-keeping, inconsistent valuation, and administrative complexity. They seem to understand that without reliable land and income records, even a well-intentioned reform may be ineffective. Meanwhile, those with lower education may view taxation primarily through its social consequences—worrying that even targeted reforms could inadvertently burden marginal farmers. This divergence points to the need for tax reform proposals that clearly communicate safeguards: for example, high exemption thresholds, phased implementation, and special provisions for smallholders. Addressing both systemic and social concerns can make reform politically and practically feasible.

From Fig 11, Higher support among highly educated respondents may reflect greater familiarity with principles of tax equity and horizontal fairness. These respondents likely distinguish between subsistence farming and commercial agribusinesses with substantial profit margins, aligning with constitutional values of equality and fiscal justice. Their views echo past policy recommendations that suggest retaining exemptions for genuinely vulnerable farmers while taxing high-income agriculturists. The slightly lower support among less-educated respondents may stem from concerns about unintended consequences, fear of administrative misuse, or lack of awareness of proposed safeguards. This underlines the importance of targeted policy communication to reassure the wider population that reforms aim to correct inequity without harming smallholders.

From Fig 12, Different occupational backgrounds shape distinct concerns about feasibility and fairness. Students and academics, who engage more with policy literature, highlight systemic record-keeping and valuation gaps. Entrepreneurs and government employees, who deal practically with compliance and administration, see challenges in reaching millions of small farmers spread across diverse agro-climatic zones, as well as volatility from unpredictable weather. These nuanced perspectives illustrate why tax reform requires multi-layered solutions: digital land records to improve accuracy, simplified presumptive taxation for small farmers, and robust valuation guidelines for large farms. Recognizing these diverse concerns can help policymakers design practical and broadly acceptable reforms.

From Fig 13, This high level of agreement among professionals likely reflects their direct exposure to the tax system and awareness of how exemptions narrow the tax base. Entrepreneurs may also recognize that tax advantages to large farmers can distort competition and resource allocation. Their views reinforce the idea that blanket exemptions are out of step with modern tax policy, which generally seeks to tax economic capacity, regardless of sector. The finding supports reform proposals that exempt smallholders but require large commercial farms to contribute, aligning with international practices where farm income above a reasonable threshold is taxed to ensure fairness.

From Fig 14, Urban respondents, likely removed from daily farming realities, view reform mainly through the lens of governance and administrative capability. They focus on technical gaps such as inconsistent record-keeping, valuation disputes, and evasion risk. Rural respondents, directly or indirectly linked to farming, prioritize socio-economic consequences, fearing that taxation could reduce net income for smallholder families, affect food security, or lead to rural distress. This contrast highlights the delicate policy balance needed: ensuring administrative capacity to enforce targeted taxation while preserving the original social purpose of exemptions—to protect genuine small and marginal farmers from financial hardship.

From Fig 15, Urban and semi-urban respondents may view agricultural tax exemptions primarily as fiscal inequities, especially when large farmers enjoy tax-free status despite high incomes. Rural respondents, shaped by direct agricultural exposure, remain cautious, fearing that reforms—even if targeted—could creep into taxing small farmers. This tension illustrates why reforms must be carefully framed: communicating that taxation will apply only above high thresholds, coupled with measures to modernize record-keeping and reduce compliance burdens. Policy messaging must clearly explain that the goal is not to tax smallholders, but to curb misuse and ensure wealthier agriculturists contribute fairly.

CONCLUSION

The taxation of agricultural income in India represents a complex intersection of constitutional design, historical policy choices, and evolving socio-economic realities. Initially justified to protect small and marginal farmers from undue financial burden, the broad exemption under Section 10(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 has, over decades, revealed significant structural weaknesses. This research critically traced the evolution of agricultural income taxation, highlighting how rising commercialization, corporatization, and large-scale agribusiness models have outpaced the legal framework’s capacity to ensure fiscal equity and prevent misuse. Comparative analysis with other countries shows that a complete exemption of agricultural income is increasingly rare. Nations like the United States and United Kingdom tax agricultural profits alongside other income while offering sector-specific deductions, whereas countries such as China abolished direct agricultural taxes but supplemented rural development through alternative fiscal tools. These approaches illustrate that balanced, targeted taxation can coexist with rural welfare objectives.

Findings from this study underscore that the constitutional distribution of taxing powers, combined with political sensitivities and administrative challenges—particularly outdated land records and valuation issues—have hindered reform in India. Yet expert bodies like the Wanchoo Committee (1971), Kelkar Task Force (2002), and contemporary scholars have consistently recommended threshold-based taxation, better definitions of “agricultural income,” and integration into the broader tax system to prevent revenue leakage and inequity. Recent government initiatives—such as digitization of land records through DILRMP, efforts to redefine taxable agricultural activities, and policy debates around taxing high-income agriculturists—indicate a cautious but notable shift towards reform. The study concludes that India must move towards a balanced model: maintaining high exemption thresholds to protect genuine small farmers while effectively taxing large agricultural incomes, composite business models, and high-value plantation profits.

Such reform would not only broaden India’s narrow tax base but also promote fairness by ensuring that tax privileges benefit to those truly intended. Ultimately, aligning agricultural taxation with contemporary economic realities and constitutional values of equity and justice is both a fiscal necessity and a moral imperative in a rapidly transforming rural economy.

REFERENCES

- Gandhi, V. P. (1969). Taxation of Agricultural Income under Central Income Tax. Economic and Political Weekly, 4(31), 1234–1242. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23214949

- James, E. (2004). Policy Options for the Taxation of Agricultural Land and Agricultural Income in India. Asia-Pacific Tax Bulletin.

- Rajaraman, I. (2005). Taxing Agriculture in a Developing Country: A Possible Approach. National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

- Khan, S. (2001). Agricultural Taxation in Developing Countries: A Survey of Issues and Policy. Journal of International Development, 13(1), 89–106.

- OECD. (2020). Taxation in Agriculture. https://www.oecd.org/tax/taxation-in-agriculture.htm

- Schwerhoff, G., Edenhofer, O., & Fleurbaey, M. (2022). Equity and Efficiency Effects of Land Value Taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 206, 104591.

- Muellbauer, J. (2023). Why We Need a Green Land-Value Tax and How to Design It. Fiscal Studies, 44(1), 1–24.

- Novak, J. (2019). Land Value Taxation as Anti-Speculation Measure. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(5), 639–654.

- Turner, B. (2019). Urban Land-Value Taxation: Lessons for Sustainable Cities. Urban Policy and Research, 37(2), 120–134.

- Anderson, K., & Browne, M. (2021). Environmental Levies in Agricultural Policy: A Comparative Review. Environmental Policy and Governance, 31(3), 191–203.

- Martinez-Alier, J., et al. (2021). Ecological Fiscal Reform: Environmental Taxes in Latin American Agriculture. Ecological Economics, 180, 106871.

- Peterson, G. (2022). Split-Rate Property Tax: Merging Land and Improvements in Rural Context. Land Use Policy, 112, 105808.

- Ribeiro, F., & Silva, J. (2023). Sustainable Land and Agriculture Taxation in Portugal. Land Use Policy, 129, 106601.

- Green, R., & Patel, S. (2020). Aligning Agricultural Taxes with Climate Policy. Environmental Tax Review, 31(2), 56–68.

- Li, Y., & Wang, H. (2020). Integrating Land and Agriculture Taxes in China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 12(3), 475–491.

- Smith, J., & Johnson, P. (2018). A Comparative Study of Land-Value Tax Models in Europe. Public Finance Review, 46(6), 881–905.

- Trumboo, A. (2022). Agricultural Income Tax in India: Introducing Threshold-Based Tax Exemption. Economic and Political Weekly, 57(14).

- Dr. Pradip Kumar Das. (2024). Taxability of Agricultural Income in India: A Study. Journal of Indian Law and Society.

- Oluwaremilekun A. Adebisi et al. (2021). Effect of Farm Income on the Lifestyle Factors of Farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria. Agricultural Economics.

- Kovalchuk, A., et al. (2021). Legal Regulation of Agricultural Taxation. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(3), 123–134. https://ojs.ecsdev.org/index.php/ejsd/article/view/1185

- https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/injlolw11§ion=230

- https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/injlolw11&div=592&id=&page=

- https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:GMH-cayGA8UJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5#d=gs_qabs&t=1751534418820&u=%23p%3DyQN-6Mm_H6sJ

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/23214949

- Wanchoo Committee Report (1971). Government of India.

- Kelkar Task Force Report (2002). Government of India.

- OECD (2020). Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation. https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/agricultural-policy-monitoring-and-evaluation/

- Government of India. (2025). Income Tax Bill 2025. https://businesstoday.in/personal-finance/tax/story/income-tax-bill-2025-heres-how-taxation-of-agricultural-income-farmland-has-been-tweaked-464590-2025-02-13

- Government of India. (2025). Union Budget 2025–26 Highlights. https://firstpost.com/explainers/big-tax-relief-middle-class-push-agriculture-msmes-takeaways-union-budget-2025-2026-13858607.html