Author(s): Samyukktha S

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 3

Citation: IJLSSS 3(3) 01

Page No: Page 01 – 08

ABSTRACT

Despite legal abolition, bonded labour continues to thrive in parts of India under disguised and informal arrangements. Bonded labour remains one of India’s most deep-rooted and persistent human rights violations, despite being legally abolished nearly five decades ago. Disguised within modern economic structures, this exploitative system persists in targeting vulnerable groups, especially migrant workers, Scheduled Castes, and Tribal populations. Rooted in poverty, debt, and social inequality, this practice traps vulnerable communities in cycles of forced labour and exploitation. Although laws like the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 and Article 23 of the Constitution prohibit such practices, enforcement remains inconsistent and rehabilitation efforts are often delayed or inadequate. This article highlights the present-day manifestations of bonded labour and outlines a forward-looking strategy that includes legal reform, community awareness, and better implementation. The road ahead calls for both strong governance and grassroots engagement to permanently end this form of modern-day slavery.

Keywords—Legal aboliton, Human Rights violation, Marginalized community, Legal reform, Abolition, Article and Modern day slavery.

INTRODUCTION

Bonded labour, often referred to as debt bondage or slavery, involves compelling an individual to work in order to settle a debt or fulfill an obligation, typically under coercive conditions.

Although the Bonded Labour System was officially outlawed in India through the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act of 1976, it continues to persist in hidden ways across sectors such as agriculture, brick-making, construction, garment production, and domestic services. It primarily affects economically and socially marginalized communities, forcing individuals to work under coercive conditions to repay debts that are often manipulated to remain unending. Across generations, families often remain trapped in an ongoing cycle of deprivation and coercive labour.

Despite constitutional safeguards and judicial interventions, enforcement on the ground remains weak. This paper explores the persistence of bonded labour in contemporary India, highlights key shortcomings in the enforcement of existing legal safeguards, and outlines actionable steps toward building a fairer, more inclusive society—where the promise of freedom from exploitation is fully realized in practice.

What makes bonded labour particularly dangerous today is its adaptability—it now hides behind informal contracts, middlemen, and unregulated sectors, making detection and prosecution difficult.

Additionally, migrant labourers, especially post-pandemic, are more vulnerable to exploitative debt arrangements due to job insecurity and lack of documentation. The lack of accurate data and underreporting further weakens policy response. Addressing bonded labour is no longer just about abolition; it is about systemic transformation—redefining labour dignity, improving access to legal aid, and building a labour market where no one is forced to choose survival over freedom.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK IN INDIA

CURRENT SITUATION

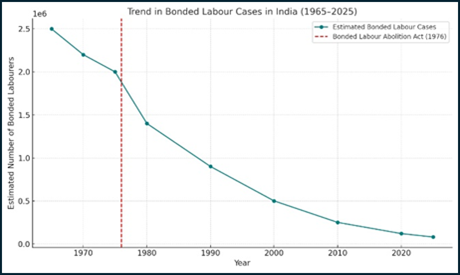

The analysis diagram of the bonded labour cases in India before and after Bonded Labour act establishment

Figure.1 Analysis of bonded labour cases in India

Bonded labour continues to be prevalent across South Asia, particularly in countries like India and Pakistan. It is especially common in sectors such as agriculture, brick-making, textiles, mining, and small-scale industries. Often intertwined with other exploitative practices like human trafficking, this form of modern-day slavery remains deeply entrenched.

As per 2022 estimates, nearly 20% of individuals in private sector forced labour situations are subjected to debt bondage. Many victims are unable to escape, living under the constant threat of violence or the burden of passing the debt to their children.

Debt bondage frequently begins with false promises, where individuals are deceived into accepting jobs that offer minimal or no wages. They may be compelled to repay inflated costs related to recruitment, food, or shelter, with no control over how the debt is calculated. Their earnings are typically absorbed entirely to cover these so-called loans.

In numerous instances, victims end up working far beyond what is required to settle their original debt, often indefinitely, without seeing a path to freedom. The economic distress brought on by the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic worsened the situation, as limited access to formal credit sources forced many into exploitative debt arrangements.

BONDED LABOUR ACT

The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 stands as a landmark legislation aimed at dismantling one of the oldest forms of human exploitation in India. Its comprehensive provisions for abolition, identification, rehabilitation, and penal action continue to inspire efforts to eradicate bonded labour in all its modern manifestations.

FEATURES OF BONDED LABOUR ACT, 1976

1. Total Abolition of the Bonded Labour System

- Declares the bonded labour system as illegal throughout India.

- All bonded labour arrangements, past or present, are null and void from the date the Act came into force (25 October 1975 in some states, nationwide by 1976).

2. Automatic Release of Bonded Labourers

- All individuals trapped in bonded labour are automatically freed without the need for court intervention.

- They are discharged from any liability to repay debts or render future services linked to bondage.

3. Extinguishment of Existing Debts

- Any debt, obligation, or liability that caused the bonded labour is considered cancelled.

- Creditors or employers cannot claim compensation for work already performed.

4. Prohibition of Future Bonded Labour Agreements

- Prohibits all future contracts or agreements that may cause a person to fall into bonded labour, including oral, written, social, or customary obligations.

5. Punitive Measures

- Enforcing bonded labour is a cognizable and punishable offense.

- Imprisonment up to 3 years, or

- Fine up to ₹2,000, or both.

- Higher penalties for repeat offenses.

6. Identification and Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers

- Mandates state and district authorities to:

- Identify bonded labourers through surveys.

- Rehabilitate them via financial aid, housing, employment, or education.

- Ensures no freed person is re-enslaved due to poverty or lack of livelihood.

7. Constitution of Vigilance Committees

- Vigilance Committees must be established at both district and sub-division levels to monitor and address bonded labour cases.

- Committees consist of:

- Local officials,

- NGO representatives,

- Social workers,

- Members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

- Their role is to monitor, rescue, and rehabilitate bonded labourers.

8. Judicial Oversight and Summary Trials

- Offenses under this Act are tried in summary courts for speedy justice.

- Courts may also issue orders for restitution or immediate release.

9. Responsibility of Employers

- Employers or contractors cannot hire or keep any bonded labourer.

- Use of intermediaries or agents to enforce debt bondage is also punishable.

10. Override on Other Laws

- The Act supersedes any local customs, traditional practices, or state legislations that legitimize or promote bonded labour in any form

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

- Article 23 of the Constitution prohibits traffic in human beings and forced labour.

- Article 21 guarantees the right to life and dignity, which extends to freedom from exploitative labour practices.

OTHER RELEVANT LAWS

- Minimum Wages Act, 1948

- Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979

- The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 plays a key role in protecting marginalized communities from exploitative labour conditions and caste-based abuse.

JUDICIAL INTERPRETATION AND CASE LAW

BANDHUA MUKTI MORCHA V. UNION OF INDIA (AIR 1984 SC 802)

This landmark PIL by a civil rights group led the Supreme Court to hold that Article 21 includes the right against bonded labour.

The Court directed the government to identify and release bonded labourers in stone quarries.

PEOPLE’S UNION FOR DEMOCRATIC RIGHTS V. UNION OF INDIA (1982)

The Supreme Court has recognized that failure to pay minimum wages constitutes a form of forced labour under Article 23 of the Indian Constitution.

IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES

Hidden & Evolving Forms

Modern bonded labour is disguised in gig work, withheld wages, and informal contracts, making it hard to detect.

Poor Identification

Authorities rely on complaints instead of active surveys; many victims remain unnoticed.

Lack of Awareness

Most bonded workers are unaware of their rights or the illegality of their situation.

Weak Rehabilitation

Freed labourers often receive no support, leading to re-bondage due to poverty.

Corruption & Collusion

Local officials may protect employers or ignore complaints, weakening enforcement.

Departmental Gaps

No coordination among labour, police, and welfare departments; efforts remain fragmented.

Slow Justice

Legal cases take years, with low conviction rates and little deterrence.

Urban Blind Spots

The law overlooks exploitation in cities—factories, domestic work, and digital platforms.

No Central Registry

Lack of a national database for rescued workers hampers tracking and policy making.

Cultural Normalization

Bondage is often accepted as tradition or duty, especially in rural and caste-based settings.

OTHER GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

It runs the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labour, offering financial aid, housing, and skill training.

District-level Vigilance Committees are set up to identify and monitor bonded labour cases.

Awareness programs and surveys are conducted in collaboration with NGOs and state bodies.

Recent efforts also focus on tracking urban and modern forms of bonded labour through technology and inter-department coordination.

FUTURISTIC GOALS AND WAY FORWARD

1. Digital Identification & Tracking

- Establish a national digital registry of rescued bonded labourers.

- Technological tools such as AI-driven monitoring and geo-tagged field inspections can help detect hidden bonded labour practices, especially within informal employment and digital gig platforms.

2. Integrated Rehabilitation Ecosystem

- Build a centralized portal that links freed labourers with skill training, housing, health care, and legal aid.

- Ensure direct cash transfers and employment guarantees to prevent re-bondage.

3. Urban Bonded Labour Surveillance

- Expand the Act’s scope to urban and platform-based exploitation.

- Appoint urban vigilance officers in high-risk areas like construction, domestic work, and delivery services.

4. Labour-Justice Fast Track Courts

- Create special fast-track courts for bonded labour cases to ensure time-bound justice and higher conviction rates.

5. Behavioural Change & Community Empowerment

- Launch grassroots awareness campaigns in high-risk regions, focusing on caste, migration, and gender-sensitive messaging.

- Empower local communities to act as first-line watchdogs through Panchayat-level action groups.

6. Cross-Border & Inter-State Coordination

- Develop inter-state task forces to trace trafficking chains and migrant bondage.

- Strengthen cooperation with neighbouring countries to curb transnational bonded labour rings.

India’s fight against bonded labour must shift from reactive rescue to preventive, tech-enabled, and community-driven systems. With legal reform, digital tools, economic inclusion, and strong enforcement, India can move towards total eradication of bonded labour by the end of this decade.

CONCLUSION

While India has made significant legal strides in abolishing bonded labour, the practice continues in new, concealed forms. It is not only a legal violation but a human rights issue that challenges the country’s commitment to dignity, equality, and justice. The Indian Constitution expressly bans human trafficking, begar (unpaid labour), and all similar forms of coerced work; any violation of this principle is a punishable criminal offence under the law. A coordinated effort involving legal reform, vigilant enforcement, community participation, and robust rehabilitation is crucial to eliminate bonded labour permanently.