Author(s): Shruthika. S

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 3

Citation: IJLSSS 3(3) 08

Page No: 121 – 141

ABSTRACT

Cryptocurrency, a revolutionary technology in the era of decentralized finance, has inadvertently created a fertile ground for new and sophisticated forms of criminal activity. This article critically examines the evolving typologies of crypto-related crimes, dissecting the methods used by malicious actors and highlighting the legal and regulatory voids that allow such schemes to flourish. From rug pulls to Ponzi schemes, phishing, and spoofing, the article explores how the anonymity, decentralization, and lack of intermediaries in blockchain technology are being misused for nefarious purposes in the absence of robust legal and regulatory paradigms. The article analyzes the global enforcement landscape, jurisdictional dilemmas, and technological complexities involved in investigating and prosecuting crypto offenses, revealing a legal system ill-equipped to deal with borderless, decentralized, and anonymous financial crimes. The article also examines the psychological toll on victims of crypto fraud, who are often left without recourse or recovery due to the lack of legal recognition and institutional support. By analyzing case studies, current legal frameworks, and emerging global trends, the article proposes strategic reforms and potential regulatory frameworks to bolster consumer protection, strengthen legal accountability, and restore integrity to crypto-based transactions. The article concludes by emphasizing the need for a comprehensive legal overhaul of financial crime, taking into account the long-term nature of cryptocurrency and the transient nature of existing enforcement systems, to prevent systemic vulnerability and punish wrongdoing in the digital economy.

KEYWORDS: Cryptocurrency, Ponzi schemes, Blockchain, Financial crime, Digital Economy

INTRODUCTION: A PROMISE HIJACKED

In 2008, the mysterious figure known as Satoshi Nakamoto revealed Bitcoin in a whitepaper that laid out the fundamental and radical proposition to create “A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash” that allowed people to transact without any middlemen and, in effect, wield control of their own finances without any central authority. For the increasing numbers of people dissatisfied with everything from the recent economic collapse that had exposed the fragility of banks to alleged infiltration of the public by the NSA, Nakamoto’s promise of an alternative to centralised financial systems sounded promising, to say the least.

Fifteen years later, we find ourselves in a gigantic crypto expansion. With a total market capitalisation surpassing the $2 trillion mark in 2024, not using digital assets in global financial conversations makes one seem out of touch. Cryptocurrencies are no longer fringe financial instruments; they are now being used for all sorts of thing at every level of the economy: for cross-border transactions, as investment vehicles, on decentralised lending platforms, and (in some jurisdictions) for everyday payments. But where there is expansion, there is also bound to be fraud and deception, and the crypto space seems to be a particularly fertile ground for those activities.

The decentralised nature of blockchain once considered its most democratic and disruptive characteristic has ironically become its weakest point. The lack of a central regulatory authority often allows perpetrators of bad behaviour to almost freely do bad deeds. Illegal schemes such as rug pulls, exit scams, and Ponzi arrangements play up the legal grey area in which cryptocurrencies find themselves in many nations, including India. A 2023 report by the Financial Crime Academy doesn’t just lump these schemes as the latest in crypto criminality; it says the schemes have become a whole lot smarter, leveraging not just tech loopholes but also cleverly manipulating and targeting human nature.

This issue is pressing, especially in India. The Supreme Court, in Internet and Mobile Association of India v. RBI (2020), struck down the RBI’s blanket banking ban on crypto. But it did not resolve the underlying problem of the complete absence of a legislative framework to regulate virtual assets. India lacks legislation specifically defining and classifying cryptocurrencies to this 2024, hence creating a regulatory vacuum that draws criminal elements and exposes investors to risk.

What makes these crimes so dangerous is the aura of legitimacy they sport so frequently. Crypto scams are almost always delivered with the trappings of professional marketing, celebrity sponsorship, and techno-utopian buzzwords. Victims are not merely technologically unsophisticated investors; even professionals have been caught on platforms that guarantee stratospheric yields. Having already been swindled, these investors are then left to deal with a legal system that is all too often inadequately resourced, underfunded, and sometimes even rather clueless about how to track down or retrieve digital assets lost in the decentralised wilderness.

This article tries to de-mystify the rising prevalence of criminality in the world of cryptocurrency by examining how the very characteristics of blockchain technology, anonymity, decentralisation, and lack of middlemen, can be misused for nefarious purposes in the absence of robust legal and regulatory paradigms. By way of case studies, current legal paradigms (or lack thereof), and emerging global trends, the article examines how the law can evolve to protect consumers and uphold the integrity of an originally liberatory technology now on the cusp of turning into a lawless frontier.

As crypto culture expands, so does our imagination within the law. At stake is not merely the security of online transactions, but the integrity of technological innovation itself.

CRYPTO CRIMINAL SPECTRUM: FROM RUG PULLS TO DIGITAL PYRAMID EMPIRES

The decentralised nature of blockchain technology, while revolutionary, has created fertile ground for new and sophisticated forms of criminal activity. Unlike traditional financial frauds, which often require access to regulated institutions or networks, cryptocurrency fraudsters exploit the borderless, pseudonymous, and unregulated attributes of this digital infrastructure. What emerges is a parallel ecosystem that is deceptively democratic, but deeply vulnerable. The cryptocrime spectrum is vast, but certain recurring patterns illustrate the innovative yet devastating tactics employed by perpetrators.

1. RUG PULLS: THE MIRAGE OF A PROMISING PROJECT

One of the most rampant forms of crypto fraud in decentralised finance (DeFi) is rug pull. In such schemes, developers create new cryptocurrency tokens, often launching them with impressive websites, detailed whitepapers, influencer endorsements, and promises of high returns. Investors, lured by Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), pour in liquidity, and then, overnight, the developers withdraw all funds and disappear.

These scams thrive in DeFi platforms where decentralised exchanges (DEXs) allow anyone to list a token without regulatory vetting. In 2023 alone, rug pulls accounted for approximately 35% of DeFi-related crypto scams worldwide, according to a report by Fintech News Asia (2024). The infamous case of Squid Coin, which capitalised on the popularity of the Netflix series Squid Game, is a cautionary tale. After raising millions, the developers abruptly shut down the project, leaving investors with worthless tokens.

Legally, rug pulls challenge enforcement because many developers operate anonymously, across borders, and on platforms that lack central governance. Victims are left not only financially devastated but also without clear legal remedies due to the anonymity of perpetrators and lack of formal agreements.

2. PONZI AND PYRAMID SCHEMES: OLD SCAMS IN NEW CODE

Using cryptocurrency, the older Ponzi and pyramid schemes have found a new virtual look. These frauds promise atrocious returns that occur out of the capital-one of newer investors- rather than from any actual genuine activity of business. What gave them more sting during the crypto era was their global reach, lack of barriers to entry, and a veil of respectability put on them by the blockchain technology.

Arguably the most significant was BitConnect, which started its prosecution in 2016 and died in 2018. Promoted as a “high-yield investment program,” it promised fabulous returns of 40% per month through an automated trading bot. The crash of BitConnect saw a loss of investor wealth worth approximately $3.5 billion USD. Due to the complexities involved in asset recovery operations across borders, most victims are yet to see restitution.

These schemes wear the hat of innovation smart contracts, affiliate marketing, tokenomics but are essentially scams. Marked by the Financial Crime Academy (2023) as capitalizing on the “techno-literacy gap” of investors, they are dazzled by jargon but very much ignorant of the legal risk involved.

3. EXIT SCAMS AND SPOOFING: THE VANISHING ACT

Though the exit scam is another widespread type of fraud often perpetrated in the context of ICOs. Companies in ICOs raise funds by issuing their own crypto tokens to investors. While many are legitimate, the absence of hard-wired due diligence mechanisms allows fake ICOs to raise millions-and disappear without a trace.

Modern Tech, a Vietnamese company, criminally raised upwards of $660 million via the Pincoin and iFan ICOs, and then disappeared with the money, leaving more than 30,000 investors defrauded. The company founders simply disappeared, and in spite of all criminal complaints, the recovery proved impossible because of the transnationality of the scam.

Spoofing is a market manipulation technique whereby unscrupulous actors place great fake buy or sell orders to create an illusion of market movement with a view to – affecting some prices. This strategy confounds investors and traders, with consequent financial damages and artificial volatility.

Such acts highlight a key legal loophole: traditional securities and commodities regulations do not often reach the crypto markets, leaving these crimes either unpunished or misclassified under outdated laws.

4. ROMANCE SCAMS AND PHISHING FRAUDS: THE EMOTIONAL TRAP

Even as technological frauds vie for headline attention, crypto-based romance scams and phishing attacks remind us that human frailty is at the heart of many crimes. In these scams, clients are targeted through dating platforms, social media, or messenger applications. The con artist impersonates a potential romantic partner and slowly builds trust and eventually persuades the victim to invest in fake crypto trading platforms or to transfer assets to fraudulent wallets.

Phishing scams take place quite literally. The criminals in Phishing send emails, websites, or links that copy a legitimate crypto exchange or wallet. Once the user has entered credentials or seed phrases, the fraudsters then take control of the victim’s funds, usually forever.

According to Fintech News Asia (2024), these social engineering-based scams comprised a large bulk of the retail-level crypto crimes in Southeast Asia, with India witnessing a rise in similar cases after 2021.

The law gets confused since these embezzlements usually combine psychological manipulation with technological exploitation. Victims may feel ashamed or hesitant to report them, and where these do get reported, tracing the stolen crypto asset flow will call for advanced blockchain analytics and international collaboration- resources of which most local police units are bare of.

From rug pulls to Ponzi schemes, phishing, and spoofing, what connects all of them is an absence of accountability provided ever so conveniently with the decentralised architecture of blockchain. In the state of traditional finance, banks, brokers, and regulators serve as intermediaries who ensure compliance and expose violations for recourse; in crypto, decentralisation means those intermediaries are not there, and in many instances, code takes the place of the law.

5. UNIFYING THREAD: DECENTRALISED ANONYMITY, DISAPPEARING ACCOUNTABILITY

From rug pulls to Ponzi schemes, phishing, and spoofing, what connects all of them is an absence of accountability provided ever so conveniently with the decentralised architecture of blockchain. In the state of traditional finance, banks, brokers, and regulators serve as intermediaries who ensure compliance and expose violations for recourse; in crypto, decentralisation means those intermediaries are not there, and in many instances, code takes the place of the law.

More importantly, most crypto transactions are pseudonymous; while they are recorded on a public ledger, they do not identify the real-world actors behind them. In short, anonymity, speed, and global access are a dangerous combination, drawing borderless: a criminal playground and legal jurisdictions.

As Tiwari (2024) observes in his SSRN working paper, Cryptocurrency and Crime: A Legal Inquiry, “decentralisation is not inherently lawless but without a supporting legal infrastructure, it becomes a tool for impunity.”

WHY LAW LAGS: A LEGAL FRAMEWORK OUTPACED BY INNOVATION

Because of lightning-fast evolution in cryptocurrency and blockchain technology, the legal mechanisms in any country have never kept pace with the technology. While the crypto-markets trade in billions on a daily basis[1], the laws theorized to regulate such markets remain fragmented, disjointed, not fully developed, or almost non-existent in jurisdictions[2]. This mismatch between tech advancements and regulatory inertia has created a legal void in which ill-intentioned people prosper, those who suffer are left without remedy, and enforcement agencies are left to pursue shadows in a jurisdictional gridlock[3].

INDIA: A CASE STUDY IN LEGAL AMBIGUITY

In India, the legal treatment of cryptocurrency is a story of uncertainty and shifting positions[4]. In 2018, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a circular prohibiting banks and financial institutions from dealing in, including from providing any service in relation to, virtual currencies[5]. This move was widely perceived as a de facto ban inhibiting innovation behind closed doors while pushing legitimate crypto activity underground[6].

In 2020, however, the Supreme Court, in Internet and Mobile Association of India v. Reserve Bank of India, (2020)[7], passed a judgment striking down the RBI’s circular. The Court opined that the prohibition was disproportionate and violative of Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom to practice any profession or carry on any trade or business[8]. The decision was hailed as a win for innovation; however, it did not even deal with the fundamental issue of having no statutory regime governing cryptocurrencies[9].

India still does not have a legislative classification or definition of crypto assets. They are neither legal tender, nor prohibited outright[10]. This state of uncertainty puts the regulators, courts, and police in a quandary. Offences against digital assets like fraud, money laundering, or cyber theft have to be prosecuted under conventional penal legislation, e.g., Indian Penal Code (IPC), Information Technology Act, 2000, or Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002[11]. None of these legislations, however, were ever intended to deal with borderless, decentralised, and anonymous financial instruments[12].

This lack of dedicated crypto laws leads to a lack of legal certainty, inconsistent court interpretations, and effective enforcement challenges[13]. For example, even when a rug pull scam is from India, the scammers tend to operate through VPNs, anonymous wallets, and decentralized exchanges (DEXs) located overseas[14]. The victims are left in procedural limbo unable to track stolen funds, report adequately, or launch timely prosecutions[15].

What is needed in the hour is a committed legal tool a version of a “Cryptocurrency Regulation and Protection Act” which would establish a definition of crypto assets, provide sanction for registration, institute anti-money laundering measures, and institutionalize a central body for regulatory oversight and grievance redressal[16]. Until then, innovation and investor protection are hostages to regulatory indecision[17].

THE GLOBAL PUZZLE: A BORDERLESS CRIME MEETS BORDERED LAWS

Meanwhile, as India struggles with legal ambiguity, the international scene is similarly divided. Cryptocurrency is, in its nature, a borderless technology, but the legal frameworks that regulate it are heavily territorial. Criminals take advantage of this disconnect with surgical exactness.[18]

In accordance with the Financial Crime Academy (2023),

“Crypto crime is intrinsically transnational, and the lack of harmonised regulations makes it possible for regulatory arbitrage, whereby criminals channel transactions through jurisdictions with the weakest enforcement.” [19]

Most scammed crypto platforms are registered in countries with weak supervision or expressly operate as Decentralised Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) that have no existence in any form[20]. When a crime is committed, investigators will discover that the criminal has their base in one nation, the victim in another, and the server in a third.[21] In these situations, current bilateral treaties, mutual legal assistance agreements, and Interpol protocols are too slow or insufficient to provide any real-time solution.[22]

For instance, a defrauded Indian investor in a token project run from Seychelles that was listed on a DEX based on Dutch servers may see no obvious route to pursue action or get their money back. Even where there are blockchain analytic tools tracing wallets, the absence of cross-border enforcement cooperation holds action back.[23] Further, most domestic legislation does not treat smart contracts or DAOs as entities under the law, leaving loopholes that protect criminal activities.[24]

A few jurisdictions, the European Union among them, have moved ahead early with harmonisation through its draft Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) regulation. MiCA aims to establish a common framework for regulating crypto assets in EU member states, covering licensing conditions, consumer protection, and anti-money laundering requirements.[25] Others, like Singapore and Japan, have also passed more definitive rules that cover crypto exchanges and ICOs. These are, however, exceptions rather than the rule.[26]

India, with its strong fintech and tech environment, still sits on the periphery of this global regulatory shift. The government had enacted a 30% flat tax on virtual digital assets in 2022, and a 1% TDS on transfers, but these actions are fiscal in nature—rather than protective. They view cryptocurrency as a source of revenue, not as a sector that merits regulation or legal definition.[27]

LAW ENFORCEMENT: ILL-EQUIPPED FOR A NEW KIND OF CRIME

Aside from laws, even the institutional machinery to investigate and prosecute crypto offenses is ill-equipped. Police forces in India typically lack both the technology competence and forensic equipment needed to trace digital purses, decrypt blockchain footprints, or even work with global agencies.[28] FIRs for crypto frauds are routinely rejected or filed under vague IT offences, and no specialized cyber prosecutors with expertise in blockchain crime exist.[29]

At the same time, the criminals become more advanced. They utilize tumbling services, mixer websites, privacy coins, and multi-signature vaults to wash ill-gotten gains.[30]They take advantage of the fact that most DeFi platforms lack a central authority, and they tend to rename and resurface quicker than enforcement can catch up.[31]

LEGAL LABYRINTH: INVESTIGATING THE UNTRACEABLE

The design of the blockchain open, decentralized, and borderless is usually hailed as a wonder of technological advancement. But this same design that facilitates transparency and autonomy creates a nightmare for law enforcement agencies and courts in terms of investigation and prosecution. Unlike the conventional financial fraud, the crimes involving cryptocurrencies are not merely monetary losses but are about evidence embedded in code, spread across nodes, and wrapped in anonymity. The law system, based on material tracks and jurisdictional lines, is having difficulty penetrating this virtual labyrinth.

1. PSEUDONYMITY VS. ANONYMITY: A DELICATE LINE BETWEEN TRACEABLE AND UNTRACEABLE

Blockchain technology is pseudonymous, not anonymous. All transactions are inscribed on a public ledger, dated, and associated with a digital wallet address. On paper, this is a forensic investigator’s dream an unalterable audit trail dating back to the genesis block.[32] In practice, though, these wallet addresses commonly contain no names, locations, or personal identifiers. [33]Unless a suspect has already associated his or her wallet with a centralised exchange (CEX) that is complying with Know Your Customer (KYC) standards, law enforcement reaches a roadblock.[34]

Even where such transactions are involved, receiving KYC information involves legal coordination between jurisdictions, and most crypto exchanges either have their headquarters in offshoring havens or run without adequate compliance. According to Fintech News Asia (2024), “The absence of uniform global KYC enforcement standards enables malicious actors to easily evade identification protocols.”[35]

This phenomenon has created what experts refer to as the “crypto veil” a cover of protection that enables scammers to run visible wallets but be invisible actors. Law enforcers sometimes find themselves tracking wallets without ever revealing who is behind them.[36] Most of the time, suspects just transfer assets through a chain of tumblers or “mixers” essentially laundering them and causing the trail to go cold.[37]

2. THE DECENTRALISATION DILEMMA: WHOM DO YOU SUBPOENA?

In traditional financial crimes, investigators subpoena bank records, freeze accounts, or get wiretap authorisations. These mechanisms are based on the presence of central intermediaries’ entities that manage the flow of funds or information.[38] But in decentralised finance (DeFi), there are no such intermediaries. Platforms operate based on smart contracts posted on public blockchains, ruled by nobody and accessible to everybody.[39]

This decentralisation leaves a legal blackhole. Without a CEO to question, no server farm to raid, and no headquarters to serve notice, enforcement agencies are left with a target that is unclear. For example, a rug pull scam run through a smart contract on Ethereum might have thousands of participants based all around the world, but no “issuer” to identify.[40]

Furthermore, most such sites have auto-liquidation tools and self-executing code such that reversing transactions, even by a court order, is impossible. In such a scenario, even if wrongdoing has been perpetrated, the restitution tool or tool of freezing assets are effectively rendered useless.[41]

3. SMART CONTRACTS AND DAO FRAUD: WHEN THE CODE GOES ROGUE

Smart contracts self-executing contracts whose terms are written directly into code form the foundation of DeFi platforms. While they obviate the intermediary, they also pose a fundamental legal question: If “code is law,” who bears responsibility when the code malfunctions, gets hacked, or is coded maliciously?

This quandary entered international prominence with The DAO hack in 2016, where an attacker took advantage of a vulnerability in a smart contract in Ethereum’s largest decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO) to drain about $60 million worth of Ether.[42] The governance of The DAO was fully code-based. No human imposter deliberately broke rules. Rather, a design flaw was employed to carry out what was arguably “allowed” by the contract logic.[43]

In such situations, legal liability is fuzzy. Is the developer at fault for poor code? Is the user at fault for taking advantage of it? Or is the agreement guilty? Courts, particularly in jurisdictions such as India, have no precedent or statutory framework to chart such techno-legal dilemmas. [44]There is no legal personality given to DAOs, and smart contracts are not yet recognized as legally enforceable contracts under Indian law.[45]

4. THE EVIDENTIARY CHALLENGE: COURTS IN A PRE-BLOCKCHAIN ERA

Even if law enforcement detects a crypto fraud, proving it in court is still dauntingly high. Blockchain-based evidence is technical in nature, lengthy, and usually incomprehensible to attorneys and judges. In contrast to traditional documents or email trails, crypto fraud evidence can contain transaction hashes, smart contract exploits, consensus attack histories, and wallet forensics each of which needs to be expertly explained.

As Yuvraj Tiwari (2024) points out in his SSRN paper “Blockchain, Crime, and the Courtroom: Legal Gaps in Admissibility and Comprehension,” judicial blockchain illiteracy is a systemic obstacle to justice.[46] Trials are stuck with prosecutors vainly attempting to elucidate the chain of transactions, or worse, defence counsels taking advantage of judicial ignorance to create doubt or prolong proceedings.[47]This results in crypto crime cases getting cold despite the technical leads.

Additionally, the chain of custody crucial to digital evidence is hard to establish when investigators themselves do not have the cyber-forensic equipment to secure and authenticate blockchain information from the very beginning. Unless India invests in judicial training modules, special prosecutors, and specialized cyberbenches, courts will continue to be ill-equipped to settle blockchain-based crimes.

THE VICTIM’S VOID: NO RECOURSE, NO RECOVERY

In the grand architecture of financial regulation, the victims have always been at the center of institutional design at least in theory. Traditional financial scams like the Harshad Mehta securities scam (1992) [48]or the Sahara chit fund case elicited strong reactions from the regulatory institutions like SEBI, RBI, and the judiciary. These institutions provided arenas of restitution, class-action suits, and, in some cases, state-monitored schemes of compensation. But the crypto universe has no such refuge. The victim of a crypto scam is not merely robbed of money they are also abandoned by law, regulators, and infrastructure.

THE DISEMPOWERED VICTIM: BEYOND LEGAL RECOGNITION

The victims of crypto fraud not only face financial loss but also extreme denial of legal redress. Within the Indian legislative framework, cryptocurrencies find no exhaustive recognition as either a “security” under SEBI or as “currency” under RBI control[49].Additionally, the Information Technology Act of 2000 does not deal with decentralized assets within its current paradigm and does not have transparent channels of redressal in the event of fraud with digital tokens.

This ambiguity is such that a victim in crypto is not even able to lodge an FIR under the correct offence category. Is it cheating under Section 420 of the IPC? A violation of trust? A cybercrime? Or mere poor investment skills? This ambiguity typically becomes the cause of police inaction, buck-passing by bureaucracy, and, ultimately, a legal vacuum in which justice is unavailable or determined.[50]

NO INSTITUTIONAL RECOURSE: WHERE DO YOU COMPLAIN

In mainstream banking or stock market environments, frustrated investors have a well-established system to take advantage of recourse: internal redressal mechanisms, the Banking Grievance Redressal, SEBI’s SCORES system, and even investor protection funds[51]. In the world of cryptocurrency, however, it is an unregulated frontier. In the event of scam operations, such as rug pulls or exit scams, there is no ombudsman, consumer forum, appellate tribunal, and usually no apparent counterparty.

Even when the victim is aware of how to detect the platform or wallet that swindled them, recovery is a losing battle. No insurance policy exists to cover digital asset thefts. Central banks and financial authorities wash their hands of such robberies, citing the absence of legal recognition[52]. Victims are, in effect, told, “you should have known better.”

This regulatory indifference transforms victims from legal subjects into mere spectators, watching helplessly as their savings vanish into the blockchain abyss.

GLOBAL LANDSCAPE: REGULATORY HALF-MEASURES AND DELAYS

Some jurisdictions have made some attempts at consumer protection. The Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation (2023) of the European Union was much heralded as a first-ever attempt to legally integrate crypto[53]. It lays out provisions for stablecoins, service providers, investor disclosures, among others. However, MiCA stops short of outrightly regulating DeFi, which leaves a huge front of the ecosystem grey.

While that being said, India has paradoxically been taxing crypto while giving no substantial regulations for it. The Budget 2022-23 had introduced a flat rate of 30% tax on all crypto profit and 1% TDS on transactions, treating digital assets as a source of speculative income[54]. Yet, there were no definitions in any financial legislation for cryptocurrencies nor enforcement agencies were created to oversee these transactions or protect investors.

This creates a “tax without recognition” paradox legitimising revenue extraction from a market that the statute itself does not officially recognise or protect. Such a policy signals do not caution, but abdication[55]. As duly noted in the analysis by Mondaq (2024) India’s crypto fledged stands out as “an unfinished bridge built from the middle, with no clear end in sight.”

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL TOLL: SCAMS BEYOND SCREENS

What is quite often lost when talking about crypto crime is the emotional devastation the victims go through. Many are retail investors, small traders, young tech-savvy individuals, and even first-time earners, drawn in by the utopian promises of financial autonomy.

The agrieved enter economic losses and additions of shame, guilt, and silence upon being cheated. Unlike bank fraud victims, who may seek recovery from institutions, crypto victims are usually told that they should have known better, thereby increasing their isolation.[56]

Other than outright refusal to report their case, crypto-fraud victims tend to fear ridicule and assure such a dynamic of refusal exists, especially in jurisdictions lacking a legal or social safety net for speculative digital assets, as stated by the Financial Crime Academy.

BRIDGING THE BLACKHOLE: TOWARDS CRYPTO-LEGAL SYNCHRONY

The rising tide of crypto fraud cannot be stopped by tearing down the technology; it can be stopped by dissecting its risks and designing a parallel legal architecture that can grow with the innovation. Whenever the law has been unable to keep pace with technology, the vacant space became a breeding ground for exploitation. In the stoppage of cryptocurrency, such vacuum is a blackhole for accountability, regulation, and justice. To bridge this gap, we must stop asking whether crypto should exist and instead focus on how it can coexist responsibly within the rule of law.[57]

DEFINING THE DIGITAL: LEGAL CATEGORISATION OF CRYPTO ASSETS

Currently, India has no statutory definition as to what constitutes a “crypto asset.” The ambiguity is the root cause of enforcement paralysis.[58] A comprehensive legal framework must classify crypto tokens based on function and risk, for example:

- Payment Tokens (e.g., Bitcoin, Litecoin): Digital substitutes for money.

- Utility Tokens (e.g., Filecoin, BAT): Grant access to services or platforms.

- Security Tokens (e.g., tokenised equity or debt): Investment contracts offering profits.[59]

Where a type of digital asset falls has real bearing on some regulator being assigned in charge—RBI, SEBI, or a crypto authority. The approach, therefore, is called after the model laid down by the EU’s proposed MiCA Regulation[60] and an approach also followed by countries such as Switzerland[61] and Singapore[62], thus providing clarity not just to investors but also courts and law enforcement agencies.

On the other hand, an Indian-originating legislation such as a “Digital Assets Regulation and Protection Act” must codify consumers’ rights, duties of intermediaries, penalties for fraud, and dispute resolution mechanisms.[63]

GLOBAL CRIME NEEDS GLOBAL LAW: CROSS-BORDER ENFORCEMENT PROTOCOLS

Crypto crimes have no borders. A rug pull launched from Vietnam could decimate investors in Mumbai; a phishing scam could route its profits via mixers in Estonia and anonymizers in the Cayman Islands.Legislating alone will not suffice. There needs to be urgent multilateral cooperation, akin to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, which comprises more than 60 countries at present but lacks any focus on cryptocurrencies.[64]

India ought to support or procure to join an endeavour to draw up a UN-sponsored convention on Crypto Asset Regulation and Enforcement that enables countries to:

- Share forensic and KYC data over secure platforms.

- Mutually recognise and enforce standards for digital evidence.

- Establish rapid-response cross-jurisdiction teams to freeze wallets or reverse transactions prior to obfuscation.[65]

Until such frameworks are in place, fraudsters will continue to exploit jurisdictional loopholes with impunity.[66]

COMPULSORY KYC/AML NORMS FOR CRYPTO ENTITIES

Decentralisation need not imply deregulation. All crypto exchanges, wallets, and DeFi platforms operating in India or offering services to residents of the country should be brought under a mandatory licensing framework that ensures:

- Know your customer (KYC): Verifiable onboarding of users via Aadhaar, passport, or any other authenticated system.[67]

- Anti-Money Laundering (AML): Implement software that monitors transactions and automatically flags suspicious transfers, and reports movement involved in large-value transfers of cryptocurrency to a central agency (such as FIU-IND).[68]

- Suspicious Transaction Reporting (STR): Updates another enforcement agency regularly, much like banks and NBFCs do[69].

Non-compliance should result in criminal prosecution, platform ban, and asset freeze. Currently, these are much of the self-regulation, voluntary, or are avoided by merely shifting offshore, and this loophole should be plugged.[70]

CRYPTO CRIMEWAVE 2021–2025: A BORDERLESS EPIDEMIC, A BOUNDED

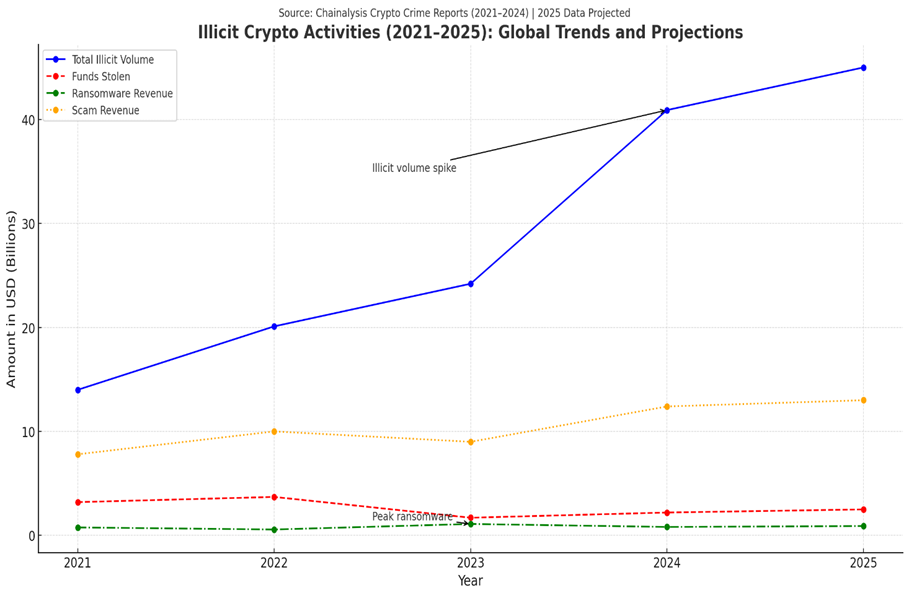

Over the past few years, the world of cryptocurrency has moved away from niche innovation towards mainstream adoption—but at a cost. As the technology grew internationally, so did the abuse. The Chainalysis Crypto Crime Reports (2021–2024), with estimates extending to 2025, uncover an alarming trend: total illicit volume has gone over $45 billion, a new record high in digital financial crime. Worse still is the fact that the increase is not limited to a single type of misconduct it cuts across scams, ransomware, stolen funds, and new-fangled exploits such as rug pulls and phishing-based wallet drains.

Source: Chain Analysis Crypto Crime Report (2021- Till March-2025)

The inflection point arrived in the 2023-2024 timeframe, as illustrated in the chart below. This sudden eruption of illicit volume was supplemented by increasing crypto adoption, the implosion of large,centralized exchanges, and the deliberate transition of cybercrime groups into DeFi platforms. Ransomware profits, while declining, remain consistent, and profit from scams is increasing once more, demonstrating the adaptation not death of fraud tactics.

In spite of this remarkable boom in international criminality, legal systems across the globe are still patchy, reactive, and in most cases, ineffective. Most countries, including India, have chosen to heavily tax crypto transactions (such as India’s 30% flat tax), but provide no meaningful regulatory protection or relief arrangements to the victims. This “tax without legal recognition” paradox justifies revenue the state accumulates while freeing it from responsibility when its users are cheated.

Whereas the perpetrators enjoy anonymity and freedom, victims anything from novice investors to pensioners are shut out of the restitution system. Official mechanisms such as consumer tribunals, insurance, or ombudsman schemes are not available to crypto victims. Police, burdened by jurisdictional uncertainty and technicality, are not typically capable of investigating, much less prosecuting.

This is a misalignment of the scope of crime and the scope of regulation that reveals a fundamental fault in regulating digital assets: finance has been globalized through technology, law remains territorial. The outcome is an ad-hoc reaction to a system threat where cybercriminals are organized across borders, but victims are trapped in legal silos. Unless international cooperation, digital evidence protocols, and crypto-specific enforcement mechanisms are created and deployed quickly, this graph would be the new normal, not an anomaly.

Therefore, the future requires not only policy assessment, but an entire multilateral legal overhaul of financial crime, taking into account the long-term nature of cryptocurrency and also the transient nature of existing enforcement systems. CONCLUSION: FROM DARN

CONCLUSION: FROM DARK CHAIN TO LEGAL CHAIN

Cryptocurrency is no longer a basically emerging disruptor-it is an up-and-coming legal challenge to contend with. As a law student, it is the fraudulence on such a massive scale that just strikes me, along with the fact that law remains quiet against all of this. From rug pulls to decentralised Ponzi systems, the digital economy has empowered criminals to exploit legal grey zones across jurisdictions. What was meant to be a vehicle of financial empowerment is hurled into opacity and firmware of unchecked greed.

Here we are at the crossroads. One road lead into a digital Wild West where innovation carries on ahead of regulation. The other offers a concerted response; a legal chain embedded within the digital chain where transparency and accountability walk alongside technology.

Cryptocurrency is beyond borders, yet crimes cannot be beyond laws. The legal system must, however, evolve to prevent systemic vulnerability along with punishing wrongdoing. We need not fear decentralisation; rather we need to govern it wisely.

REFERENCE

- Alhaidari, Abdulrahman, et al. SolRPDS: A Dataset for Analyzing Rug Pulls in Solana Decentralized Finance. 6 Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2504.07132.

- Angrish, Anil Kumar, and Sanjeev K. Bansal. “Cryptocurrencies in India : A Perspective.” Research Bulletin, vol. 47, no. 1–2, Jan. 2022, p. 51, https://doi.org/10.33516/rb.v47i1-2.51-66p.

- Angrish, Anil Kumar, and Sanjeev K. Bansal. “Cryptocurrencies in India : A Perspective.” Research Bulletin, vol. 47, no. 1–2, Jan. 2022, p. 51, https://doi.org/10.33516/rb.v47i1-2.51-66p.

- Arrizky, Bintang Juannita, and Hendri Hermawan Adinugraha. “Factors That Influence People to Take Loans from Mobile Banks.” JURNAL AL-QARDH, vol. 9, no. 1, July 2024, pp. 50–57, https://doi.org/10.23971/jaq.v9i1.8245.

- Bartoletti, Massimo, et al. “Cryptocurrency Scams: Analysis and Perspectives.” IEEE Access, vol. 9, Jan. 2021, pp. 148353–73, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3123894.

- Bolfing, Andreas. Bitcoin. oxford university pressoxford, 2020, pp. 241–58, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198862840.003.0007.

- Cabral Saisse, Renan. “Bitcoin.” Direito & TI, vol. 1, no. 6, Oct. 2016, p. 12, https://doi.org/10.63451/ti.v1i6.46.

- Cernera, Federico, et al. Token Spammers, Rug Pulls, and SniperBots: An Analysis of the Ecosystem of Tokens in Ethereum and in the Binance Smart Chain (BNB). 16 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2206.08202.

- Chiluwa, Isioma Maureen. “Truth,” Lies, and Deception in Ponzi and Pyramid Schemes. igi global, 2019, pp. 439–58, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-8535-0.ch023.

- Depoortère, Christophe. “Examining the Writings of Satoshi Nakamoto: A Monetary Analysis of the Bitcoin Protocol.” Review of Political Economy, vol. 37, no. 2, Oct. 2024, pp. 392–411, https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2024.2415413.

- Gupta, Mandeep. “Negative Impact of Ponzi Schemes on Crypto-Market.” Scientific Journal of Metaverse and Blockchain Technologies, vol. 2, no. 2, July 2024, pp. 32–42, https://doi.org/10.36676/sjmbt.v2.i2.30.

- Huang, Jintao, et al. “Miracle or Mirage? A Measurement Study of NFT Rug Pulls.” Proceedings of the ACM on Measurement and Analysis of Computing Systems, vol. 7, no. 3, Dec. 2023, pp. 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1145/3626782.

- India Backs Blockchain but Adoption Will Be Cautious. May 2018, https://doi.org/10.1108/oxan-db233975.

- Janetzko, Dietmar, et al. On the Involvement of Bots in Promote-Hit-and-Run Scams – The Case of Rug Pulls. universitat politecnica de valencia, 2023, pp. 187–94, https://doi.org/10.4995/carma2023.2023.16428.

- Janetzko, Dietmar, et al. On the Involvement of Bots in Promote-Hit-and-Run Scams – The Case of Rug Pulls. universitat politecnica de valencia, 2023, pp. 187–94, https://doi.org/10.4995/carma2023.2023.16428.

- Kashyap, Amit, et al. Integrating Cryptocurrencies to Legal and Financial Framework of India. no. 1, Mar. 2021, pp. 121–37, https://doi.org/10.14666/2194-7759-10-1-008.

- Lin, Zewei, et al. “CRPWarner: Warning the Risk of Contract-Related Rug Pull in DeFi Smart Contracts.” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 50, no. 6, June 2024, pp. 1534–47, https://doi.org/10.1109/tse.2024.3392451.

- Mehdi, Saiyed Mohd Sadiq. “Formulation of a Regulatory Regime for Cryptocurrencies in India.” MINDSHARE: International Journal of Research and Development, Dec. 2021, pp. 133–41, https://doi.org/10.55031/mshare.2021.39.lw.11.

- R, Bhuvana, and P. S. Aithal. “RBI Distributed Ledger Technology and Blockchain – A Future of Decentralized India.” International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences, May 2020, pp. 227–37, https://doi.org/10.47992/ijmts.2581.6012.0091.

- Reddy, Bhuvana, and P. Aithal. “RBI Distributed Ledger Technology and Blockchain – A Future of Decentralized India.” Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research), May 2020, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3839780.

- Sakas, Damianos P., et al. “Assessing the Efficacy of Cryptocurrency Applications’ Affiliate Marketing Process on Supply Chain Firms’ Website Visibility.” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 9, Apr. 2023, p. 7326, https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097326.

- Sharma, Renuka, et al. Cryptocurrency Adoption Behaviour of Millennial Investors in India. igi global, 2023, pp. 135–58, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-8361-9.ch006.

- Sharma, Trishie, et al. “Understanding Rug Pulls: An In-Depth Behavioral Analysis of Fraudulent NFT Creators.” ACM Transactions on the Web, vol. 18, no. 1, Oct. 2023, pp. 1–39, https://doi.org/10.1145/3623376.

- Sharma, Trishie, et al. Understanding Rug Pulls: An In-Depth Behavioral Analysis of Fraudulent NFT Creators. cornell university, 15 Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2304.07598.

- Taher, Hadeel, and Ahmad Subhi. Artificial Neural Networks Technical Transaction for Bitcoin(BTC ). shbk lmw tmrt l rby, 2018, https://doi.org/10.24897/acn.64.68.172.

- The Blockchain Technology. united nations, 2021, pp. 2–9, https://doi.org/10.18356/9789214030430c004.

- Wallace, Victoria, and Sandra Scott-Hayward. Can SDN Deanonymize Bitcoin Users? institute of electrical electronics engineers, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/icc40277.2020.9148936.

- Wang, Haoyu, et al. A Deep Dive into NFT Rug Pulls. cornell university, 10 May 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2305.06108.

- Wu, Brian, and Bridget Wu. Bitcoin: The Future of Money. apress, 2022, pp. 77–134, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-8808-5_3.

[1] Sandeep Soni, India’s Crypto Conundrum: Regulation Stuck in Limbo as Crypto Crimes Rise, Business Today, (Nov. 2023), https://www.businesstoday.in/technology/news/story/crypto-crime-cases-on-the-rise-in-india-amid-absence-of-regulations-403438-2023-11-03.

[2] Shivangi Aggarwal, The Legal Status of Cryptocurrencies in India: Existing Gaps and Future Prospects, International Journal of Law and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2023, pp. 49–63.

[3] Arjun Gargeyas, India’s Regulatory Vacuum on Crypto: Challenges and the Path Ahead, Observer Research Foundation (ORF), (Jan. 2024), https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/crypto-regulation-india/.

[4] Nikhil Pahwa, Crypto Regulation in India: A Timeline and the Way Forward, Medianama, (Feb. 2023), https://www.medianama.com/2023/02/223-india-crypto-regulation-timeline/.

[5]Reserve Bank of India, Circular on Prohibition on Dealing in Virtual Currencies, (April 6, 2018), https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11243&Mode=0.

[6] Rahul Matthan, The Supreme Court’s Verdict on the RBI Circular: A Watershed Moment for Crypto in India, The Indian Express, (Mar. 2020), https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/cryptocurrency-supreme-court-verdict-6299053/.

[7] (2020 SCC online SC 275)

[8] Ibid.

[9] Nishith Desai Associates, Cryptocurrency in India: From Ban to Boom? (Legal and Regulatory Analysis), Research Paper, (2023), https://www.nishithdesai.com/fileadmin/user_upload/pdfs/Research_Papers/Cryptocurrency_in_India.pdf.

[10] Tanvi Ratna, Why India Needs a Dedicated Crypto Legislation, Carnegie India, (2022), https://carnegieindia.org/2022/01/13/why-india-needs-dedicated-crypto-legislation-pub-86137.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Arjun Gargeyas, India’s Regulatory Vacuum on Crypto, supra note 3.

[14] Sandeep Soni, India’s Crypto Conundrum, supra note 1.

[15] Shivangi Aggarwal, The Legal Status of Cryptocurrencies in India, supra note 2.

[16] Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Assets and VASPs, (Oct. 2021), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Guidance-rba-virtual-assets-2021.html.

[17] Tanvi Ratna, Why India Needs a Dedicated Crypto Legislation, supra note 10.

[18] Chainalysis, 2024 Crypto Crime Report: Introduction, Chainalysis Blog (Feb. 7, 2024), https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/2024-crypto-crime-report-introduction/.

[19] Financial Crime Academy, Crypto Crime: A Borderless Threat, FCA Report (2023), https://financialcrimeacademy.org.

[20] Primavera De Filippi & Aaron Wright, Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code 103–109 (Harvard Univ. Press 2018).

[21] Ibid.

[22] INTERPOL, Cryptocurrency and Cybercrime Report 2023, at 19–22, https://www.interpol.int.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Nishith Desai Associates, India: Legal, Tax and Regulatory Analysis of Cryptocurrencies 33–36 (2023), https://www.nishithdesai.com.

[25]Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-assets, COM(2020) 593 final (Sept. 24, 2020).

[26] Monetary Authority of Singapore, Guidelines on Digital Token Offerings, MAS (2017); FSA Japan, Crypto Asset Regulation Summary (2023).

[27]Reserve Bank of India, Press Note on Virtual Digital Asset Taxation, RBI/2022-2023/540 (Feb. 2022).

[28] Nishith Desai Associates, supra note 7, at 37–39.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Elliptic, DeFi: Future of Finance or Criminal Playground? Elliptic Report (2023), https://www.elliptic.co.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Chainalysis, 2024 Crypto Crime Report: Introduction, Chainalysis Blog (Feb. 7, 2024), https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/2024-crypto-crime-report-introduction.

[33] Primavera De Filippi & Aaron Wright, Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code 89–95 (Harvard Univ. Press 2018).

[34] Interpol, Cryptocurrency and Cybercrime Report 2023, at 17–22 (2023), https://www.interpol.int.

[35] Fintech News Asia, Why Global KYC Gaps Are Fueling Crypto Crime, (Mar. 2024), https://fintechnews.sg.

[36] Elliptic, Crypto Mixers and The Crypto Veil, Elliptic Blog (2023), https://www.elliptic.co.

[37] Id.

[38] Nishith Desai Associates, Legal Analysis of DeFi and Crypto in India, at 32–34 (2023), https://www.nishithdesai.com.

[39] De Filippi & Wright, supra note 2, at 101–108.

[40] Chainalysis, supra note 1.

[41] FATF, Virtual Assets and VASP Guidance, June 2023, at 14–18, https://www.fatf-gafi.org.

[42] Nathaniel Popper, A Hack Exposes Vulnerability in Ethereum and Smart Contracts, N.Y. Times, June 17, 2016.

[43] Id.

[44] Nishith Desai Associates, supra note 7, at 40–45.

[45] Aaron Wright, Code-Based Governance: The DAO Example, Stanford J. Blockchain L. & Pol’y, Vol. 2 (2017).

[46] Yuvraj Tiwari, Blockchain, Crime, and the Courtroom: Legal Gaps in Admissibility and Comprehension, SSRN Working Paper (2024), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=4750983.

[47] Id. at 15–18.

[48] Securities and Exchange Board of India v. Sahara India Real Estate Corp. Ltd., (2012) 10 SCC 603; SEBI Annual Reports 1992–93 (regarding the Harshad Mehta case).

[49] Reserve Bank of India, “RBI Cautions Users of Virtual Currencies” (Dec. 24, 2013); Securities and Exchange Board of India, FAQs on Securities (2022).

[50]Apar Gupta, “Crypto and the Legal Vacuum: A Crisis of Enforcement,” Indian Journal of Law and Technology (2023).

[51]SEBI Complaints Redress System (SCORES), https://scores.gov.in; RBI Integrated Ombudsman Scheme, 2021.

[52] Press Trust of India, “RBI Says Crypto Not Recognized, No Redress Mechanism Exists,” The Economic Times (Feb. 2023).

[53] Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA), OJ L 150, 9.6.2023.

[54]Union Budget 2022-23, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Tax Proposals.

[55]Mondaq Editorial Board, “India’s Crypto Conundrum: Tax Without Recognition,” Mondaq Insights (2024), https://www.mondaq.com.

[56] Financial Crime Academy, “Crypto Crime Victims and the Emotional Fallout,” F.C.A. Research Bulletin (2023).

[57]Arvind Narayanan et al., Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies 6 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2016).

[58] Vidya S., “Crypto Regulation in India: Where We Stand,” Observer Research Foundation (Feb. 2023), https://www.orfonline.org.

[59]Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), Guidelines on ICOs (Feb. 2018).

[60] Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA), OJ L 150, 9.6.2023.

[61] FINMA, “How are Tokens Classified and Regulated in Switzerland?” (2018).

[62] Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), “A Guide to Digital Token Offerings,” 2020.

[63] Nishith Desai Associates, “Cryptocurrency Regulation in India: The Need for a Dedicated Framework,” (2023), www.nishithdesai.com.

[64]Council of Europe, Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest Convention), ETS No. 185 (2001).

[65] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), “Crypto Assets and International Crime Cooperation,” Policy Brief (2023).

[66] John Salmon & Gordon Myers, Blockchain and Law: The Rule of Code 184 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

[67] Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Assets and VASPs (2021).

[68] FIU-IND, Guidelines on Virtual Digital Assets and Monitoring (Feb. 2023), Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

[69] Reserve Bank of India, Master Direction – Know Your Customer (KYC) Direction, 2016 (updated 2023).

[70] Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI), “Self-Regulation Isn’t Enough: The Need for Statutory Crypto Rules,” 2023.