Author(s): Peeyusha Pahal and Niladry Das

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 4

Citation: IJLSSS 3(4) 08

Page No: 64 – 75

ABSTRACT

India as a developing country still struggles with resource allocation among which court cases pendency adds the salt on the wound of people. Common people hesitate to file complain as due to the procedure being hectic and being extremely complicated. The common man faces this frustration being on any side in justice administration exhausting himself financially, emotionally and socially, the helplessness thy reaches the depth of the ocean, officially letting the common man losing the faith and trust over the justice administration, this pendency is as high as 52 million according to the National Judicial Data Grid, 2025 inclusive of all the subject matters in Indian courts at every level. This research thus aims to check the level of trust of common people along with the accessibility of justice administration, secondly, it further studies impact of the delayed justice on the individuals and lastly this research aims to check the applicability of laws on the ground in regard to the limitations. This study paper is thus based on the qualitative empirical research conducted by snowball sampling via Google Forms. This study furthermore concludes itself on the basis of literature reviews and knowledge gained from practices with measures for shortening the waiting process and speedy justice, promoting transparency in the system which can help in the reduction in the frustration of the people of India.

Keywords: Legal system, society, delay, court cases, victims, accused, complaints, justice administration.

INTRODUCTION OF INDIAN LEGAL SYSTEM

The Indian justice system operates at three levels, the first being Legislature which handles the formation of laws, second, the Executors which implement the laws on ground and lastly the justice providers on the violation of these legislature. The judiciary falls under the third category of the justice administration system. The judicial wing of justice operates with a certain hierarchy, where the people navigate their way for the concerns. The judiciary does operate on the principles of fairness, equality and justice. The Apex Court is established by the Constitution of India by the virtue of Article 124. The High courts are established by the Article 214 of the Constitution. However, there is only one apex court called as Supreme Court of India, there are total 25 number of high courts. There is total 688 districts and numerous session courts. The courts in India however paces day and night toward availing the justice to people of India, the helplessness in the system sustains.

The major cause of this helpless is delay in justice, the courts are very less in numbers, with the increasing population, it is increasingly difficult to entertain all the cases and provide rapid justice. As justice system of India on one hand does lack in the number of resources, and on the other hand India being a high population country combines together to make a system clogged with the pending cases. This clogged system of backlogs does impact the people involve in the judicial services and common people who are trying to seek help from the judiciary. The common man here is any and every man involved in the judicial case or trial as victim, accused, and convict. The friends, family and society somehow gets dragged in the loop of frustration due to unawareness, lack of transparency and long pendency of a trial.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THIS RESEARCH

This research highlights the realities of the grounds in regard of the helplessness of common people. This helplessness extends to the frustration from the operational aspect of justice administration. This research thus verifies the assumption of the common people being harassed by the delayed justice which is existing in the system for a long time. This research thus brings out the light to the existing conditions for the purpose of efficient justice administration.

HIERARCHY OF THE JUDICIARY IN INDIA

The Indian judicial system is a well-structured and hierarchical framework that ensures the administration of justice across the country. The system is based on a pyramid structure, with the Supreme Court at the apex and various subordinate courts at the base. It is designed to provide justice efficiently and uniformly throughout India, upholding the rule of law and constitutional values.

At the top of the hierarchy lies the Supreme Court of India, established under Article 124 of the Constitution. It is the highest judicial authority in the country and serves as the final court of appeal in civil, criminal, and constitutional cases. The Supreme Court also has original jurisdiction in certain matters, such as disputes between the Union and States or between different States, and issues related to the enforcement of Fundamental Rights (Article 32). It comprises the Chief Justice of India and a number of other judges, as fixed by Parliament. Its decisions are binding on all courts within India, making it the guardian of the Constitution and protector of fundamental rights. Below the Supreme Court are the High Courts, one for each state or group of states. Established under Article 214, the High Courts are the principal civil and criminal courts of original jurisdiction in their respective territories, but they primarily function as appellate courts. They supervise and oversee the functioning of subordinate courts in their jurisdiction. High Courts have both original and appellate jurisdiction and can hear cases related to civil, criminal, writ petitions, and constitutional matters. They also have the power to issue writs under Article 226 of the Constitution for the enforcement of fundamental and legal rights. High Courts consist of a Chief Justice and several other judges appointed by the President.

Under the High Courts are the District Courts, which are the main courts of civil and criminal jurisdiction at the district level. These are established by state governments in every district. A District Judge heads the civil jurisdiction, while the Sessions Judge handles criminal matters. The same individual often serves both roles as the District & Sessions Judge. District Courts serve as appellate courts for the decisions of subordinate courts and also hear original suits and trials in more serious matters.

Beneath the District Courts lie the Subordinate Courts, which include both civil and criminal courts and function under the control of the District Judge. In civil matters, the hierarchy includes:

- Senior Civil Judge Court, which handles higher-value civil disputes and appeals from Junior Civil Judges.

- Junior Civil Judge Court, which handles low-value civil cases and functions as the entry-level court in the civil judicial structure.

- In criminal matters, the hierarchy is:

- Chief Judicial Magistrate (CJM), who oversees the work of other magistrates and handles cases involving sentences of up to seven years.

- Judicial Magistrate First Class (JMFC), who can try criminal cases with imprisonment up to three years and impose fines up to a specific limit.

- Judicial Magistrate Second Class, who deals with minor criminal cases and has even more limited sentencing powers.

The Magistrate Courts deal with the bulk of criminal cases at the grassroots level, including trials for petty offenses, preliminary inquiries, and granting bail. Civil disputes at the grassroots level are handled by the Civil Judges.

There are also Specialized Courts and Tribunals within the Indian judiciary to deal with specific types of cases such as family disputes (Family Courts), commercial cases (Commercial Courts), and consumer grievances (Consumer Courts). Tribunals like the National Green Tribunal (NGT), Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT), and Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) function parallel to the court system to provide speedy and specialized justice in particular domains.

The Indian judicial system follows a strict appeal mechanism, allowing an aggrieved party to move up the hierarchy—from subordinate courts to district courts, to High Courts, and ultimately to the Supreme Court. This layered structure ensures that errors at lower levels can be reviewed and corrected by higher courts, thereby strengthening judicial accountability. Indian court system is a comprehensive and multi-tiered structure that aims to deliver justice across varying levels of complexity and jurisdiction. From the Supreme Court to subordinate magistrate courts, every level plays a crucial role in maintaining law and order, safeguarding rights, and interpreting the Constitution. The hierarchy not only brings order to the administration of justice but also ensures that every citizen has access to judicial remedies, irrespective of the nature or scale of the dispute.

THE PROBABLE RATIONALE OF PEOPLE PAIN

The loopholes in justice administration justice system are well established, the Indian Journal report of 2025[1] reveals:

- Judiciary: The judiciary has been overburdened with the trials; the pendency is as high as 15,000 cases per judge in high courts in state of Allahabad along with Madhya Pradesh. Meanwhile 1000 cases per judge of high court are pending in States of Sikkim, Tripura and Meghalaya. Even in the district level the average number of workload pins at 2,200 cases per every judge, this peaks at single judge handling 500+ cases on an average in India. Some states have it worse, as state like Uttar Pradesh struggles with 4,300, Kerala handles 3,800, whereby Karnataka manages 1,750 cases per judge and

- Prison System: 176 prisons having over 200% of occupancy which makes prisoner more crowded day by day, the pendency of the cases is assumed to be increase by 15% in the Subordinate Courts and 17% in the High Courts, establishing the grave problem of people being struck in the system without the sufficient means, although it was also reported by the journal that India has improved in terms of police staffing, the human resources of department is yet to achieve the desired target. While assumption is of rapid increase, it is difficult to tell if the government would be able to tackle all the challenges at once.

- Under-Trials: Not only the issue of overburdening with low number of judges sustains, this give rises to over 20% of undertrials being detained under the system for average years of 1-3. Which annihilates the main objective of justice administration system such as speedy justice, protecting the innocent person. Contrary it severely impacts the mental health of the people involved for which 25 psychologists are available for approximately 6 lakhs prisoners. This ratio seems impossible to succeed in the safeguarding the common man of country.

- Fundamental Human Rights: It was also mentioned by the Amitava Ray Committee 2023 that only 68% of the inmates have adequate sleeping facility showing the incapacity of prison system to hold the prisoners in the walls with basic human rights and needs. It is also implied that the basic facility cannot be provided with high number of cases, rapid overcrowding in prison system, and limited resources available. This somehow gives rise to the corruption in the system to avail the limited resources, which further deteriorates the existing prevalent conditions.

THE EMPIRICAL PART: THE EXISTING FRUSTRATION

The empirical data is collected by the snowball method in qualitative research. Total number of 28 responses were gathered from common people. Out of which 50% of the responses were from criminal cases and rest of 50% were from the civil cases. The 25% of these cases were in the courts up to 3 years, however 25% are pending in the court for more than 5 years. Almost 19% of the cases are pending the court less than 10 years however surprising percentage of 27% cases are pending more in the judicial buildings for more than 10 years.

The survey results reflect significant concerns regarding delays in the legal system, with respondents primarily attributing the causes to systemic inefficiencies. Among the 28 participants, the police were identified as the leading cause of delay (46.4%), followed closely by judges (42.9%) and advocates (39.3%). This suggests a prevailing perception that key actors within the justice delivery system are contributing to the problem. A smaller fraction of respondents pointed to lack of awareness, case backlogs, or deliberate delays by opposing parties, indicating that while structural issues dominate, procedural and tactical delays also play a role.

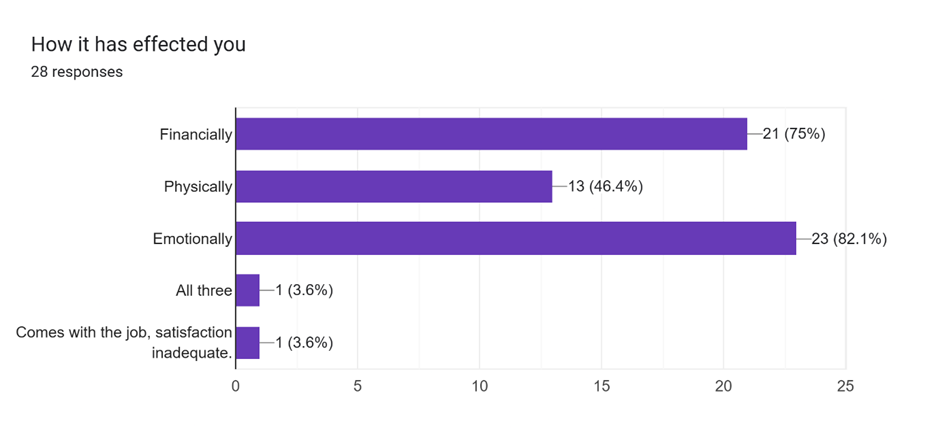

The impact of these delays on individuals is substantial. A large majority reported emotional distress (82.1%) and financial strain (75%) as primary effects, while nearly half (46.4%) experienced physical consequences. This highlights that the delays are not merely procedural hurdles but are deeply affecting people’s well-being and livelihoods. A small number also indicated that the experience diminished job satisfaction or affected them in multiple ways. Overall, the findings underscore a pressing need for reforms aimed at improving efficiency, accountability, and support within the justice system.

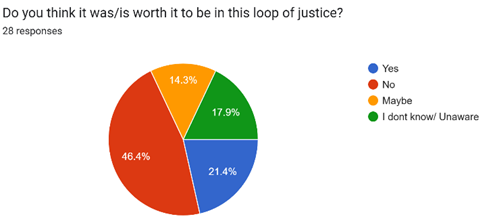

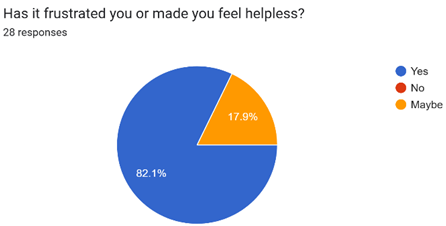

The two pie charts reflect the emotional toll and perceived futility of engaging with the justice system. In response to whether it was worth being in the legal process, only 21.4% of respondents answered “Yes”, while a significant 46.4% felt it was not worth it. An additional 17.9% were uncertain, and 14.3% admitted to being unaware or unable to assess it. This indicates a strong sense of regret or disillusionment among nearly half of the participants regarding their involvement with the justice system. The second chart further emphasizes this emotional burden. A striking 82.1% of respondents admitted to feeling frustrated or helpless due to their legal experiences, showing a clear emotional strain. Only 17.9% did not share this sentiment. Combined, the data illustrates a deep sense of dissatisfaction, hopelessness, and emotional exhaustion among those navigating the justice system, pointing to a need for more empathetic, efficient, and supportive legal processes.

The pie chart reveals that an overwhelming 92.9% of respondents feel they have no alternative to the current legal system, underscoring a sense of helplessness and lack of options. Only 3.6% believe they do have an alternative, while another 3.6% are uncertain. This overwhelming majority indicates that despite widespread dissatisfaction and emotional distress, most people feel trapped within the system, lacking viable alternatives for justice or resolution. It highlights a pressing need for accessible, effective, and trustworthy alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, and for restoring public confidence in the justice system through reforms and increased accountability.

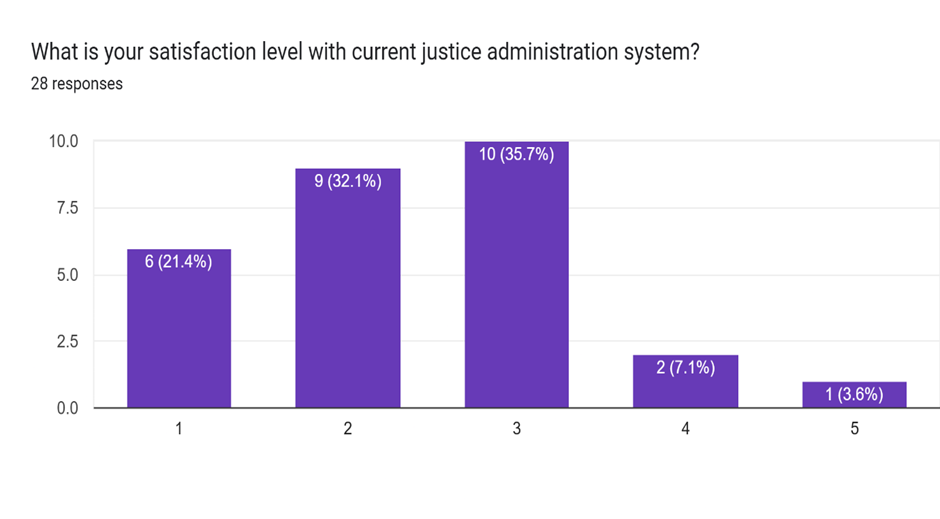

The chart reflects the respondents’ satisfaction levels with the current justice administration system, based on 28 responses. The average rating stands at a low 2.39 out of 5, clearly indicating general dissatisfaction. The majority of participants rated their satisfaction as either 2 or 3, with 32.1% selecting 2 and 35.7% choosing 3. This suggests that while most people find the system barely functional, they are not completely hopeless meaning there is room for improvement if timely reforms are introduced. Furthermore, 21.4% of respondents gave the lowest rating of 1, expressing strong dissatisfaction with the justice system. Only 7.1% gave a rating of 4, and a mere 3.6% gave the highest rating of 5, highlighting the small number of individuals who feel positively about the current state of justice administration.

The data underscores a widespread sense of frustration and disillusionment. Most respondents perceive the system as inefficient, delayed, or unresponsive to public needs. The low satisfaction scores, when viewed alongside previous charts indicating feelings of helplessness and lack of alternatives, point to a systemic failure in delivering timely and effective justice. This highlights an urgent need for systemic reforms, improved transparency, quicker case resolution, and citizen-centric approaches to rebuild public trust and improve satisfaction with the legal system.

RECOMMENDATION AND CONCLUSION

Recommendation in Tabular form:

| Issue | Recommendation | Justification |

| Low Satisfaction and Disillusionment | Streamline Legal Processes | Simplify procedures and eliminate unnecessary steps to reduce frustration and delay. |

| Time-bound Case Resolution | Implement fixed timelines for case hearings and judgments to ensure prompt resolution. | |

| Frustration and Helplessness | Increase Accessibility to Justice | Create more accessible legal aid systems and community outreach to assist individuals through the legal process. |

| Expand Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) | Offer more mediation and arbitration options to resolve cases outside of traditional courts, reducing the burden on the system. | |

| Perceived Lack of Transparency | Ensure Public Access to Court Proceedings | Implement digital platforms for case tracking, and publish judgments and status updates regularly. |

| Improve Judicial Accountability | Establish clear procedures for holding judges accountable for delays or bias in their decisions. | |

| Prolonged Delays in Case Resolution | Implement Fast-Track Courts for Specific Case Types | Designate specialized courts for cases like criminal or family law to speed up trials. |

| Invest in Judicial Capacity | Hire more judges and legal professionals to address the backlog and improve efficiency. | |

| Inadequate Communication and Support | Enhance Case Management and Communication Systems | Develop platforms that allow users to track case status, receive updates, and communicate directly with court staff. |

| Lack of Trust in the System | Foster Judicial Transparency and Public Education | Conduct public awareness campaigns to educate citizens on the judicial system’s workings and how reforms are being implemented. |

| Promote Ethics and Integrity in the Judiciary | Strengthen mechanisms for monitoring judicial conduct, ensuring impartiality and fairness. | |

| Feeling of Being Trapped | Create Alternative Legal Pathways | Promote non-court solutions and diversify the ways in which disputes can be addressed outside the traditional judicial process. |

CONCLUSION

The survey results highlight a significant and growing frustration among the public with the current state of the justice system. A large portion of the population feels that engaging with the legal process is not worth the effort, time, and emotional investment required. The overwhelming frustration, helplessness, and sense of being trapped within an inefficient system point to systemic issues that demand urgent reform. Key challenges such as prolonged delays, complex procedures, lack of transparency, and the absence of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are at the core of this dissatisfaction. These issues not only hinder the effectiveness of the justice system but also erode public trust and contribute to psychological distress among litigants. The average satisfaction rating of 2.39 underscores the deep discontent with the system’s current functionality. To address these concerns, several reforms are essential. Expedited trials and clearer outcomes must be prioritized through streamlined procedures and a focus on quicker case resolution. The expansion of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) would provide accessible, less adversarial alternatives to litigation. Improved communication and transparency are crucial to keeping litigants informed and reducing feelings of helplessness. Increasing accountability and monitoring of the judiciary is necessary to ensure fairness and prevent unnecessary delays. Simplifying court processes and expanding judicial capacity will also help reduce the complexity and backlog of cases.

Rebuilding public trust in the justice system requires bold and comprehensive changes. By implementing these measures, the legal system can regain legitimacy, foster confidence, and better serve those it was designed to protect. Ultimately, these reforms will create a justice system that is not only functional but also accessible, transparent, and equitable for all.

REFERENCES

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Mechanisms: The Role of Mediation and Arbitration in Expediting Justice

- Barton, L. (2001). Access to Justice: Reforms in the Legal System. Journal of Law and Policy, 15(3), 45-60.

- Cousins, T. (2019). Justice Delayed: The Public’s Frustration with the Court System. International Law Review, 28(4), 123-135.

- Justice Reforms and Public Confidence. (2023). National Institute of Judicial Administration.

- Miller, K. (2020). The Impact of Legal Delays on Public Trust in the Judiciary. Harvard Law Review, 29(2), 75-88.

- National Judicial Council (2022). Reforming the Legal System: A Strategic Plan for Addressing Case Backlog. NJC Reports, 34(1), 12-18.

- Parker, S. (2021). Improving Judicial Efficiency: The Role of Technology and Court Modernization. Legal Innovations Journal, 17(2), 56-70.

- Public Sentiment on Judicial Processes. (2022). Institute for Justice Research.

- Smith, R. & Adams, D. (2022). Judicial System Transparency: Increasing Public Trust Through Openness. Law and Policy, 34(4), 223-240.

- The Role of Legal Aid in Reducing Disillusionment with the Justice System. (2023). Access to Justice Foundation.

- Wright, H. (2018). Public Trust and the Erosion of Legal Confidence. Journal of Public Administration, 41(3), 203-220.

[1] Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Indian Justice Report, (2025).