Author(s): Mysoon Saifudeen and Adarsh M.V.

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 5

Citation: IJLSSS 3(5) 66

Page No: 739 – 764

INTRODUCTION: THE FRAMEWORK OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS

Geographical Indications (GIs) are vital intellectual property rights that connect products to their specific place of origin, certifying a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic essentially attributable to that geographical location.[3] The international protection of GIs is governed by agreements like the TRIPS Agreement (Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) of 1994, which defines GIs as indications that identify a good as originating in a territory, region, or locality where a specific characteristic is essentially attributable to that geographical origin.[4]

In India, the necessity for a comprehensive legal framework arose because, without protection in the country of origin, other countries had no obligation under TRIPS to extend reciprocal protection[5]. Thus, the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999 was enacted, coming into force on 15 September 2003. This legislation extends to the whole of India[6].

Unless a geographical indication is protected in its country of origin, there is no obligation under the TRIPS Agreement for other countries to extend reciprocal protection, underscoring the necessity of the domestic law to promote Indian goods in the export market[7]. The objective of providing legal protection to a geographical indication is two-fold: to protect producers from unfair competition and to protect consumers from being misled by the application of false or misleading descriptions to products[8].

For the purposes of the TRIPS Agreement (Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights), GIs are indications which identify a good as originating in a territory, region, or locality where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic is essentially attributable to its geographical origin. [9]A GI encompasses any name, geographical or figurative representation, or any combination of these, that conveys or suggests the geographical origin of the goods to which it applies[10].

CONCEPTUAL DISTINCTIONS AND SCOPE OF PROTECTION:

A geographical indication includes any name, geographical or figurative representation, or combination thereof, suggesting the geographical origin of the goods to which it applies[11]. Crucially, the Indian Act protects indications that refer to a specific geographical area, even if the name itself is not that of a country, region, or locality, such as “Basmati” rice.[12]

A. APPELLATIONS OF ORIGIN VS. GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS

The Indian Act uses the broader term “geographical indication,” which encompasses “appellations of origin” but excludes mere “indications of source”.[13]

An Appellation of Origin is a special type of GI where the characteristic qualities of the product are exclusively or essentially due to the geographical environment, including natural and human factors

A clear nexus must be established between the region of origin and the product’s characteristics, exemplified by “Darjeeling” tea, which was the first GI registered in India in 2004.[14]

The Indian GI definition is considered closer to the European concept of a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) than to that of a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). For a PGI, the product must possess a special quality, reputation, or other characteristics attributable to the area, and just one of the production, processing, or preparation steps needs to occur in that area

B. GOODS SUBJECT TO GI PROTECTION

Goods eligible for GI registration include any agricultural, natural, or manufactured goods, or any goods of handicraft or of industry, including foodstuffs.

These goods are classified according to the International Classification of Goods for the purposes of registration, specified in the Fourth Schedule, covering categories from chemicals (Class 1) to tobacco (Class 34).

Geographical indications serve a crucial developmental role by protecting the valuable reputations acquired by traditional and regional products. This protection directly supports the communities often rural and agricultural responsible for producing them, thereby reinforcing cultural heritage and economic stability.

A. PROTECTION OF TRADITIONAL SKILLS AND HUMAN FACTORS

The intrinsic link between a GI product and its origin often involves human factors, encompassing specific manufacturing skills, traditions, or specialized knowledge developed within that locality.[15] Protection ensures that these cultural practices are maintained and valued.For instance, handcrafted and industrial goods, alongside agricultural and natural products, fall under the definition of goods for GI registration

The procedural requirement for an application demands a detailed description of the human creativity involved or the particulars of special human skill associated with the GI.[16] This formal documentation legally safeguards traditional artisan and manufacturing skills, preventing generic imitation that could dilute the reputation built over generations. The protection extends even to items that carry strong cultural or religious significance, such as the Payyanur Pavithra Ring, a sacred ornament deriving sanctity from associated rituals and history of manufacture, proving that use of religious sentiment does not necessarily bar registration if the product meets GI quality criteria.[17]

B. SUPPORTING PRODUCERS AND RURAL ECONOMIES

The economic impact of GI protection primarily benefits the ‘producer.’ A “producer,” in this context, is broadly defined, covering:

1. Persons who produce, process, or package agricultural goods

2. Persons who exploit natural goods

3. Persons who make or manufacture handicraft or industrial goods, including those who trade or deal in such production.

By granting protection, unauthorized parties are excluded from misusing the GI, which prevents dishonest commercial operators from taking away valuable business from legitimate producers and damaging the established reputation of the product.

This economic shield promotes rural economic stability by securing market access and preventing fraud, thereby enabling local communities to leverage their unique geographical and human capital. The promotion of Indian GI goods in the export market is a direct intended consequence of the Act.

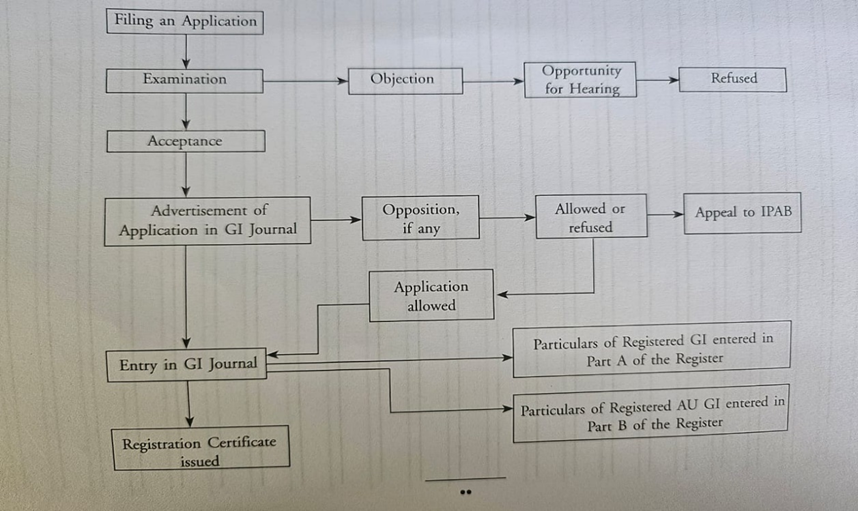

PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS: STEP-BY-STEP REGISTRATION OF A GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION

The procedural mechanisms outlined in the Act and Rules govern the application, examination, opposition, and grant of a Geographical Indication.

ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION FILING

1. ELIGIBILITY TO APPLY

An application for GI registration must be filed by any association of persons or producers or any organization or authority established by law, representing the interest of the producers of the concerned goods. The applicant must demonstrate that the producers are desirous of coming together to protect the mark and satisfy the requirements of the Act to be the Registered Proprietor.[18]

2. PLACE OF FILING

The application must be filed in the office of the Geographical Indications Registry whose territorial limits cover the territory, region, or locality to which the GI relates.[19]

If the territory is not in India, filing occurs at the Registry office corresponding to the applicant’s address for service in India.[20] Subsequent changes in the principal place of business do not affect the jurisdiction of the appropriate office.[21]

3. FORM AND PRESENTATION

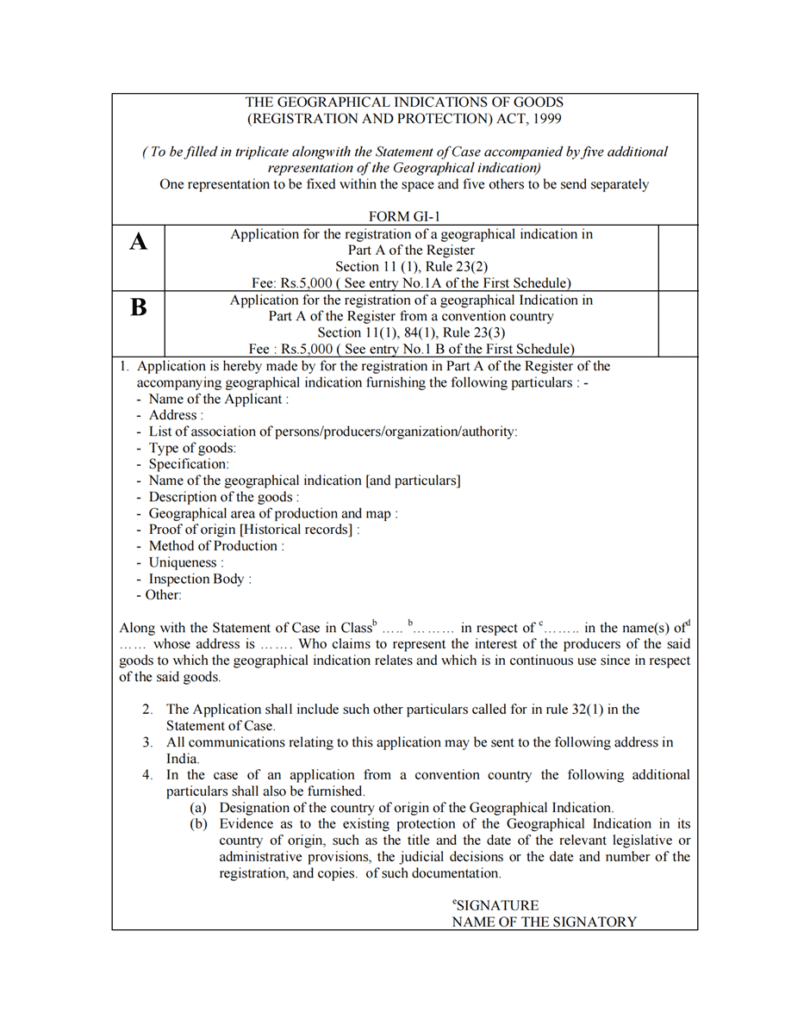

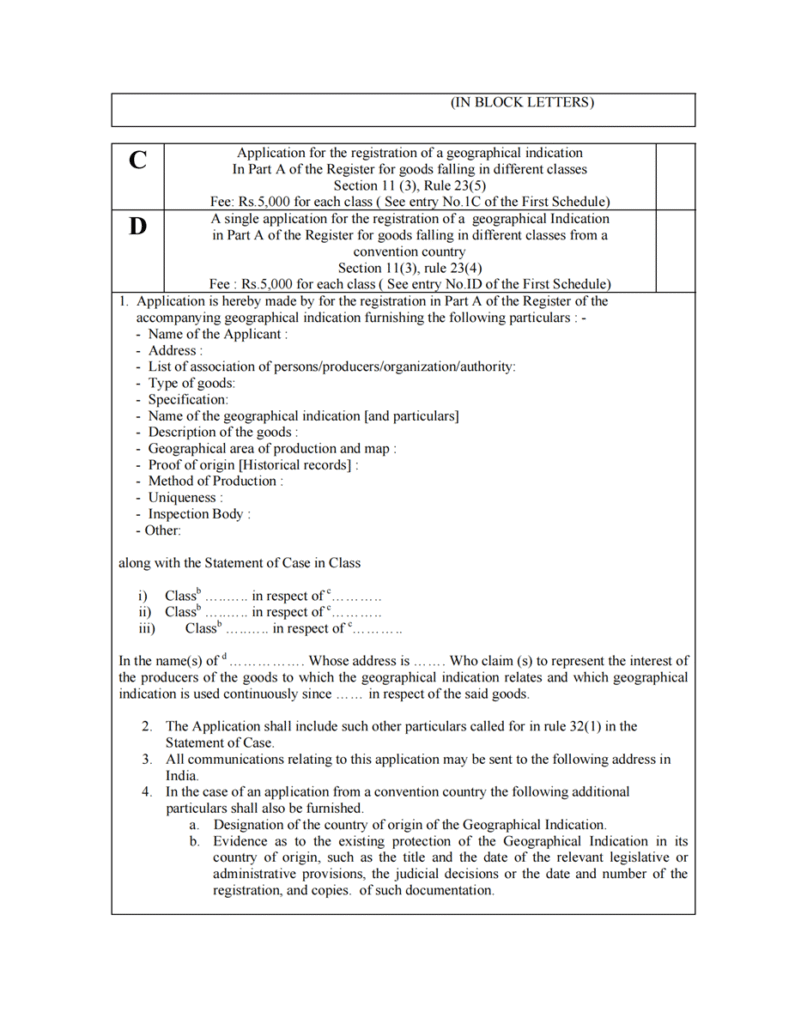

The application must be made in writing to the Registrar in the prescribed form (Form GI-1), manner, and with prescribed fees, submitted in triplicate along with three copies of a Statement of Case.[22]

The applicant must provide full names and addresses, including nationality and calling, and in the case of a body corporate, the names and nationality of the Board of Directors\footnote.[23] If the application is deficient, the Registrar issues notice, and failure to remedy deficiencies within one month may lead to the application being treated as abandoned.

CONTENTS AND FORMALITIES OF APPLICATION

The application is required to be accompanied by extensive documentation to support the claim of geographical linkage and quality control:

1. STATEMENT OF GEOGRAPHICAL LINKAGE

This is a critical statement detailing how the GI designates the goods as originating from the territory/region/locality, explaining how the specific quality, reputation, or other characteristics are due exclusively or essentially to the geographical environment, including natural and human factors.[24] It must also state that the production, processing, or preparation takes place in that defined area.

2. DETAILS OF GOODS AND TERRITORY

The application must include the class of goods to which the GI applies, specified in accordance with the Fourth Schedule classification. It must also include a geographical map (three certified copies) of the territory, region, or locality where the goods originate or are manufactured.

3. QUALITY CONTROL AND UNIQUENESS

The applicant must provide:

• Standards/Benchmark: The standards benchmark for the use of the geographical indication regarding the production, exploitation, making, or manufacture of the goods, including a detailed description of the human creativity involved.

• Inspection Mechanism: Particulars of the mechanism used to ensure that the standards, quality, integrity, and consistency of the goods are maintained by the producers, makers, or manufacturers.

• Special Skill: Particulars of the special human skill involved or the uniqueness of the geographical environment associated with the GI.

4. REPRESENTATION AND STATEMENT OF USER

The application must contain a visual representation of the GI (not exceeding 33cm by 20cm) and must be accompanied by five additional representations, all exactly corresponding.[25]A statement of the period of use and the person by whom the GI has been used must be included, supported by an affidavit testifying to such use, volume of sales, and the definite territory concerned.[26]

EXAMINATION AND ACCEPTANCE

INITIAL EXAMINATION AND CONSULTATIVE GROUP

The Registrar must examine every application and its accompanying Statement of Case to determine if it meets the requirements of the Act and Rules.[27]

For this purpose, the Registrar ordinarily constitutes a Consultative Group of not more than seven representatives to ascertain the correctness of the particulars provided in the Statement of Case. This process should usually be finalized within three months from the Group’s constitution, after which the Registrar issues an Examination Report to the applicant.

CONDITIONAL ACCEPTANCE OR DISMISSAL

The Registrar has the authority to refuse the application or accept it absolutely, or subject to amendments, modifications, conditions, or limitations.[28]If the Registrar has objections, these are communicated in writing. If the applicant fails to amend the application, submit observations, or apply for or to attend a hearing within two months, the application shall be dismissed.[29]

In case of refusal or conditional acceptance, the Registrar must record the grounds and materials used in arriving at the decision in writing.

WITHDRAWAL OF ACCEPTANCE

Even after acceptance but before registration, the Registrar may withdraw acceptance if objections arise. For example, if the acceptance occurred in error, or if the GI should be registered subject to additional or different conditions.[30]

ADVERTISEMENT AND OPPOSITION

1. ADVERTISEMENT OF APPLICATION

Once accepted (absolutely or conditionally), the application is advertised in the prescribed manner in the Geographical Indications Journal as soon as possible, ordinarily within three months of acceptance.[31]

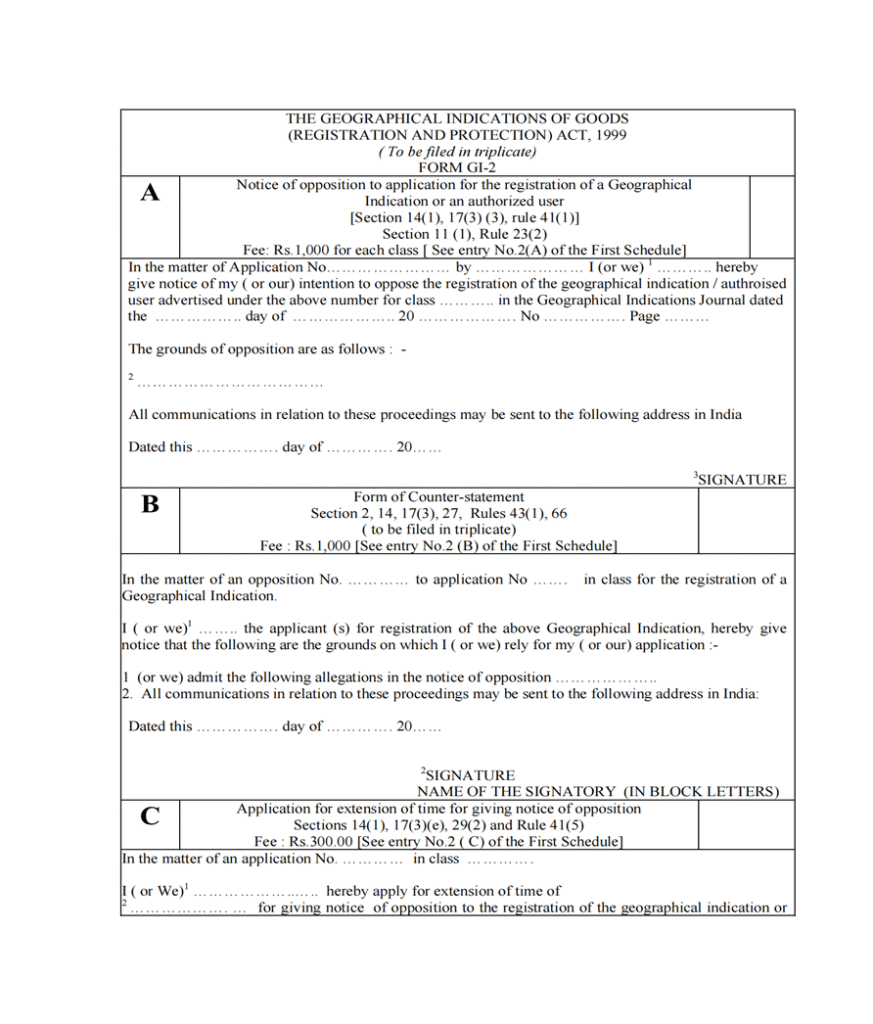

2. NOTICE OF OPPOSITION

Any person, regardless of possessing a direct personal interest (no locus standi requirement), may give notice of opposition in writing to the Registrar within three months from the date of advertisement or re-advertisement.[32]

This period may be extended by 30 days in aggregate by the Registrar

3. COUNTER-STATEMENT AND EVIDENCE EXCHANGE

Upon receiving the notice of opposition, the Registrar serves a copy on the applicant. The applicant must file a counter-statement of the grounds relied upon within 60 days of receiving the notice; failure to do so results in the application being deemed abandoned.[33]

The subsequent steps involve an exchange of evidence:

• Opponent’s Evidence: The opponent provides evidence by affidavit (or relies on facts in the notice) within two months of receiving the counter-statement, extendable by one month. If no action is taken, the opposition is deemed abandoned.[34]

• Applicant’s Evidence: The applicant responds with evidence in support of their application within two months (plus one month extension) of receiving the opponent’s evidence or intimation that no evidence will be adduced.[35]

• Opponent’s Reply: The opponent may file evidence strictly in reply within one month (plus one month extension) of receiving the applicant’s evidence

4. HEARING AND DECISION

Upon completion of the evidence, the Registrar issues a notice for a hearing, generally within three months. The Registrar, after hearing the parties and considering the evidence, decides whether and subject to what conditions the registration is permitted. The Registrar may also consider objections not relied upon by the opponent.[36]

GRANT OF REGISTRATION

When the application is accepted and either the opposition time has expired without objection, or the opposition has been decided in the applicant’s favour, the Registrar registers the GI and any authorized users mentioned in the application.[37]

The registration date is deemed to be the date of filing the original application.

If registration is not completed within 12 months due to the applicant’s default, the Registrar may treat the application as abandoned after issuing notice.

Upon registration, the Registrar issues a certificate sealed with the seal of the Geographical Indication Registry to the applicant and the authorized users (if registered.[38] This certificate serves as prima facie evidence of the validity of the GI in all legal proceedings.[39]

REGISTRATION OF AUTHORIZED USERS

Individual producers utilize the protection afforded by a GI through registration as an Authorized User. This mechanism ensures that only legitimate producers from the defined geographical area can legally benefit from the registered GI, maintaining the GI’s reputation and supporting the local producer community.

A. APPLICATION FOR AUTHORIZED USER STATUS

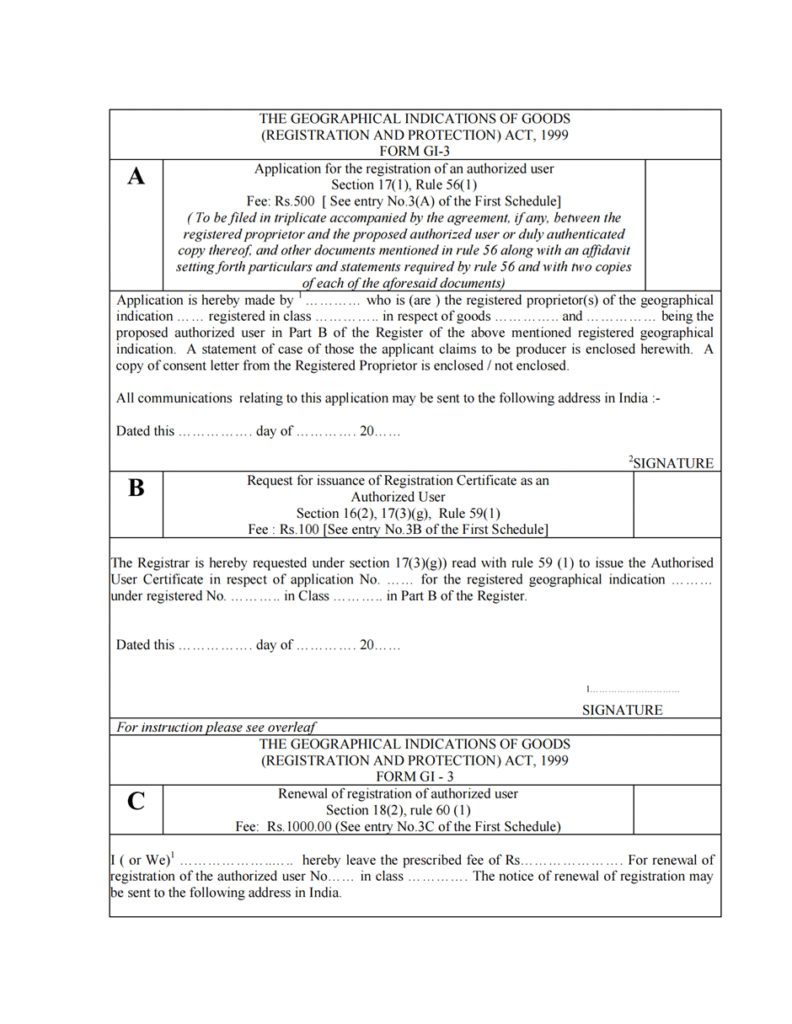

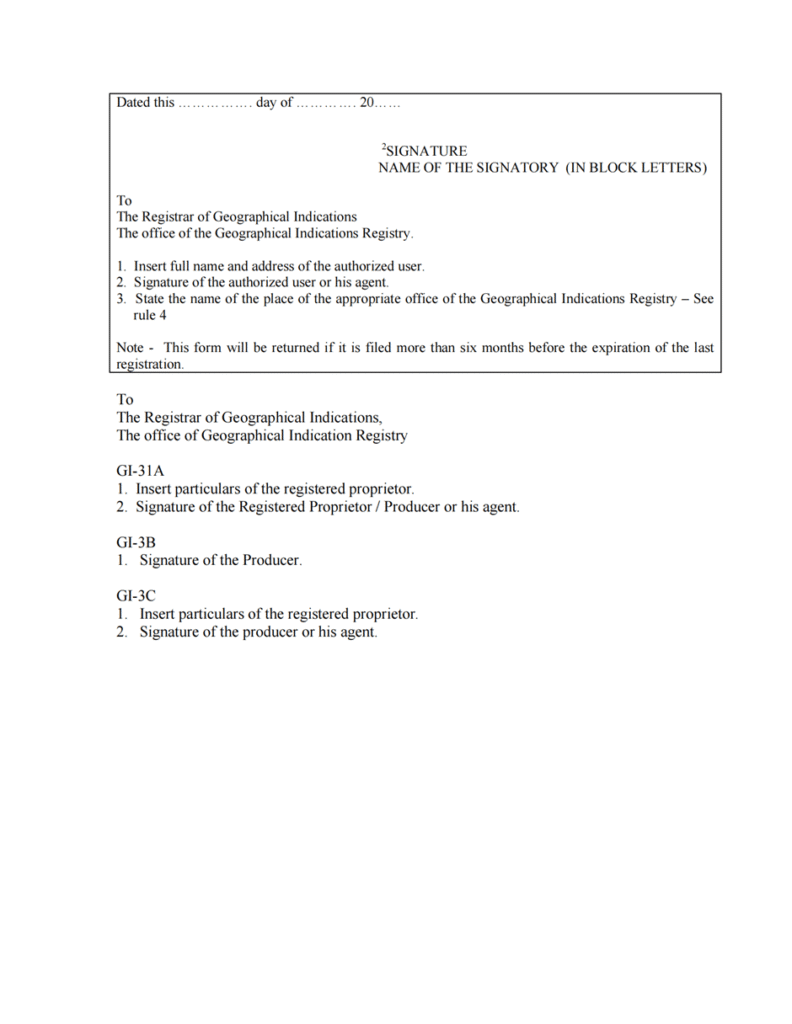

Any person claiming to be a producer of the registered goods may apply in writing to the Registrar for registration as an authorized user.[40]. The application must be made jointly by the registered proprietor and the proposed authorized user in the prescribed form (Form GI-3).[41] It must be accompanied by an affidavit containing a Statement of Case explaining how the applicant qualifies as a producer, along with a copy of the letter of consent from the registered proprietor.

B. PROSECUTION AND REGISTRATION

The procedure for prosecuting an authorised user application, including filing, examination, refusal, acceptance, advertisement, and opposition, is generally the same as the procedure for registering the geographical indication itself.

Upon completion of the procedure, the authorised user is entered into Part B of the Register.[42] The entry specifies the date of filing, the actual date of registration, the goods and class registered, and the addresses of the proprietor and user.

C. DURATION AND PROHIBITION OF TRANSFER

A GI registration is valid for 10 years and renewable.[43]

The registration of an authorized user is valid for 10 years or until the date the registration of the geographical indication expires, whichever is earlier

A critical mechanism maintaining the integrity of GIs is the prohibition of assignment or transmission. Any right to a registered geographical indication cannot be the subject matter of assignment, transmission, licensing, pledge, mortgage, or similar agreements. This ensures that the right remains intrinsically linked to the geographical origin and the representative body, though the right of an authorized user may devolve upon their successor-in-title upon death. [44]

MAINTENANCE, RENEWAL, AND THE REGISTER

Effective protection requires continuous maintenance of the registration and accurate record-keeping by the Geographical Indications Registry.

A. RENEWAL AND RESTORATION

1. RENEWAL PROCEDURE

The Registrar must notify the registered proprietor or authorized user between one and three months prior to the expiration of the current registration if no renewal application (Form GI-4 or GI-3) has been received.[45]

An application for renewal must be made by the proprietor or any registered authorized user no more than six months before expiration.[46]

Renewal extends the registration for a period of ten years from the date of expiration of the previous registration.[47] para 185.2054. If the proprietor has ceased to exist, renewal must be effected collectively by any of the authorized users listed in Part B of the register.

2. REMOVAL AND RESTORATION

If renewal conditions (including payment of fees) are not met by the time of expiration, the Registrar may remove the geographical indication or authorized user from the register.

However, restoration is possible. Where a GI or authorized user has been removed for non-payment, the Registrar may, after six months and within one year from the expiration, restore the registration upon receipt of the prescribed fee and application (Form GI-4), if satisfied that it is just to do so. The restoration is for a period of ten years from the expiration of the last registration.[48]

B. MAINTENANCE OF THE REGISTER

The Register of Geographical Indications is maintained at the Head Office of the Registry and may be kept wholly or partly on computer.[49]

It is divided into two parts:

• Part A: Consists of particulars relating to the registration of the geographical indication itself.[50]

• Part B: Incorporates particulars related to the registration of the authorized users.[51]

The Register must contain the names, addresses, and descriptions of proprietors, authorized users, and other prescribed matters.[52] The Registry also maintains indices of registered GIs, pending applications, proprietors’ names, and authorized users’ names.[53] These documents, along with opposition notices, counter-statements, and affidavits, are generally open to public inspection.

THE ROLE OF GI PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN CULTURAL AND RURAL EMPOWERMENT

The framework for Geographical Indications (GIs) is not solely focused on trade regulation; its fundamental structure compels the formal recognition and preservation of unique local characteristics, directly supporting rural economies and safeguarding cultural heritage.

ECONOMIC PROTECTION AND RURAL EMPOWERMENT

The primary function of GI protection is dual: to shield legitimate producers from unfair competition and prevent consumers from being misled by unauthorized or false product descriptions.[54] By excluding unauthorized persons from misusing GIs, the valuable business associated with the product is retained within the originating community, promoting goods in the export market and mitigating financial damage caused by worth-less imitations.[55]

This economic protection is directed toward the producer, a definition specifically tailored to cover key rural industries.[56]

- Agricultural Producers: This includes individuals who produce, process, or package agricultural goods.[57] Agricultural products are intrinsically linked to local factors such as climate and soil, emphasizing the physical dependence on the defined area.

- Natural Goods Exploiters: Persons who exploit natural goods are recognized as producers.[58]

3. Handicraft and Industrial Manufacturers: Crucially for local economies, the definition also covers persons who make or manufacture handicraft or industrial goods, including those who trade or deal in such production.

This comprehensive scope ensures that small-scale, traditional, and location-dependent economic activities are granted formal legal protection, which is essential for stabilising rural incomes and promoting regional specialised trades.

PRESERVATION OF TRADITIONAL SKILLS AND CULTURAL HERITAGE

The most significant link between GI registration and cultural preservation lies within the stringent requirements for the application itself. The law ensures that products are not only tied to the soil, but also to the accumulated knowledge and traditions of the people of that area.

1. FORMAL MANDATE TO DOCUMENT HUMAN FACTORS

When applying for registration, the applicant association must submit a detailed statement explaining how the goods’ specific quality, reputation, or other characteristics are due “exclusively or essentially to the geographical environment, with its inherent natural and human factors”.[59]

This requirement mandates the formal documentation of intangible cultural capital, including:

• A detailed description of the human creativity involved in the production, exploitation, making, or manufacture of the goods.

• Particulars of special human skill involved or the uniqueness of the geographical environment associated with the GI.

By legally obligating producers to articulate and prove the specific manufacturing skills, traditions, or other human factors that contribute to the product’s quality, the GI system formalizes the protection of local knowledge and generational techniques.

This prevents the dilution of traditional methods that are essential for maintaining the product’s authenticity and high reputation.

2. PROTECTION OF CULTURAL ARTIFACTS

The application of GI law even extends to goods with strong cultural or religious ties, provided they meet the requisite criteria. For example, in the case concerning the Payyanur Pavithra Ring a uniquely crafted ring considered a sacred ornament deriving sanctity from associated rituals and manufacturing history, the Assistant Registrar for GIs affirmed that the product was legitimate “goods of GI” and that the use of religious sentiment did not bar registration.

Although that specific registration was later dismissed on procedural grounds regarding the representative capacity of the filing association, the underlying principle confirmed the suitability of culturally and ritually significant artifacts for GI protection, highlighting the system’s role in preserving heritage objects and the specialized skills required to produce them.[60]

Thus, the procedural mechanisms of the GI Act are structured to identify, celebrate, and legally enforce the nexus between a product, its geography, and the unique human culture that has shaped it, thereby reinforcing cultural continuity and providing economic stability to the rural producers involved.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

EXPENSIVE PROCEDURE

The system that charges Multiple fees for multiple class increases the expenditure to

register a GI. For instance, if an applicant files an application for registering GI in multiple classes, for each class he has to pay a fee of Rs.5000/- for each class. Even for opponents who are opposing the registration, has to pay the fee of Rs.5000/- for each class.

MULTIPLE REGISTRATION FOR REGISTERED PROPRIETOR WHO WANTS TO USE THE GI

Any association of persons or of producers or any organisation that is registered as a

registered proprietor wants to use the GI, they have to apply for registering them as registered

user.

THE REGISTRATION OF GI AND AUTHORISED USER IS CO-TERMINUS

It is often seen that authorised users register several years after the GI go registered. But section 18(2) states that the registration of an authorised user shall be for a period of ten years or for the period till the date on which the registration of the geographical indication in respect of which the authorised user is registered expires, whichever is earlier. Because of this, an authorised user’s term might end prematurely if the GI is not renewed on time. The only option available for authorised user in such situation is to restore his title of ‘authorised user’ which again has fee to be paid.

LACK OF SYSTEM TO ENSURE THAT THE APPLICANT IS REPRESENTING THE INTEREST OF PRODUCERS

The GI Act and GI Rules do not provide specific guidelines for determining whether the claimed proprietor or producer truly represents the producers’ interests or even produces the goods in question. Notably, the GI Act allows a producer to contest an applicant’s claim if they do not truly represent producer interests. When such opposition is filed, authorities evaluate the evidence and circumstances; they have refused GI mark registration if the applicant doesn’t genuinely represent producers or seeks only commercial gain. However, there are issues with the time taken to resolve these challenges, and producers might not always be able to contest every unauthorized registration. If unauthorized registrations are not addressed, they may hinder the registration process for authorized users. Therefore, it would be advantageous to strengthen the initial requirement for applicants to prove they represent producers’ interests, reducing unauthorized registrations.

LACK OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR THE INSPECTION BODY

The application to register GI-1 suggests forming an “Inspection Body” responsible for ensuring the quality of goods under the GI. However, because the current Act doesn’t impose statutory liability on these inspection organizations for violations, it has been argued that the existing legislative framework lacks effectiveness in monitoring whether GI products meet their specifications.

Right now, the only option for collective group members authorized to use the GI, or consumers wanting to hold a member accountable for not maintaining product quality standards, is through Section 27 of the act. This section allows for the cancellation of a member’s registration from the list of authorized GI producers if they violate or fail to comply with requirements on the register, empowering the tribunal to cancel or modify the GI registration. Thus, making the inspection body legally accountable is one way to ensure the quality of GI products. One instance where the State interfered is through the creation of Basmati Rice (Quality Control and Inspection) Rules, 2003 in order to tackle the problem of inferior quality of Basmati Rice.

SCIENTIFIC BACKING IS MISSING IN THE INGREDIENTS OF APPLICATION

Scientifically unproven claims might seep in the application form. For instance “Naga mircha,” the claim that it’s “the hottest chili on earth” hasn’t been scientifically proven. Extensive research is needed to confirm the distinctiveness of such agricultural products. Many GIs lack scientific backing to its claimed speciality or uniqueness.[62]

LACK OF AWARENESS

A lack of awareness among artisans about Geographical Indication (GI) laws can lead to significant consequences that negatively impact both individual artisans and their communities.

Primarily, they may face economic losses as they miss out on the premium pricing and market opportunities that GI status could provide. Without this crucial knowledge, artisans are at risk of losing the authenticity and recognition of their unique crafts, which are often tied intricately to their geographical origins and cultural heritage. This oversight can pave the way for unauthorized use or imitation by larger companies, eroding the quality and reputation of the artisans’ work.

Additionally, without understanding GI laws, artisans can be vulnerable to exploitation by intermediaries who benefit from their ignorance, further diminishing their potential profits and bargaining power. Consequently, the lack of awareness not only stalls community development and sustainable practices but also potentially washes away traditional methods that could otherwise contribute to a vibrant cultural legacy.

CONCLUSION

India’s Geographical Indications regime is a powerful legal tool that successfully links economic development with cultural preservation. By legally protecting the unique identity of place-based products, it empowers rural producers and safeguards traditional knowledge and skills from misappropriation. The detailed procedural mechanisms ensure that only genuine products from a defined territory can benefit from the GI tag, securing market advantage and preventing consumer deception.

However, the system’s full potential is hindered by practical challenges, including a complex and costly registration process, a lack of accountability for quality control bodies, and insufficient awareness among artisans. Addressing these shortcomings through streamlined procedures, stronger oversight, and widespread awareness campaigns is essential. By doing so, the GI framework can more effectively fulfill its promise of driving sustainable rural empowerment and preserving India’s invaluable cultural heritage.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

LEGISLATION

Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999

Basmati Rice (Quality Control and Inspection) Rules 2003

INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (signed 15 April 1994, entered into force 1 January 1995) (TRIPS Agreement)

CASES

Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma v ASDA Stores Ltd [2002] UKHL 37, [2002] EWHC 2025 (Ch)

Payyannur Pavithra Ring, Artisans & Devp v K Balakrishnan (2009) 41 PTC 719 (GIG)

Subhash Jewellery v Payyannur Pavithra Ring, Artisans & Devp Society (2013) 15 PTC 197 (IPAB)

BOOKS

Halsbury’s Laws of India (Intellectual Property Rights II, 2nd edn, 2020)

Vandana Singh, The Law of Geographical Indications: Rising Above the Horizon (Eastern Law House 2017)

JOURNAL ARTICLES

Sonam SK and Hussain M, ‘Commercialization of Indigenous Health Drinks as Geographical Indications’ (2011) 16 Journal of Intellectual Property Rights 170

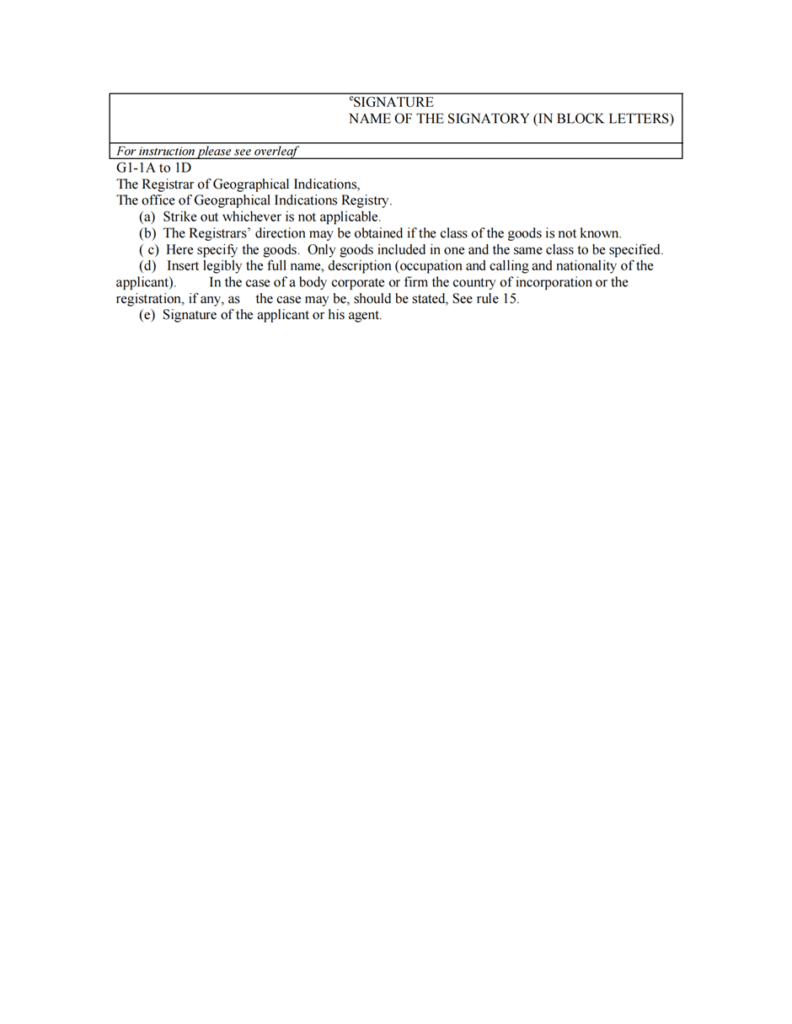

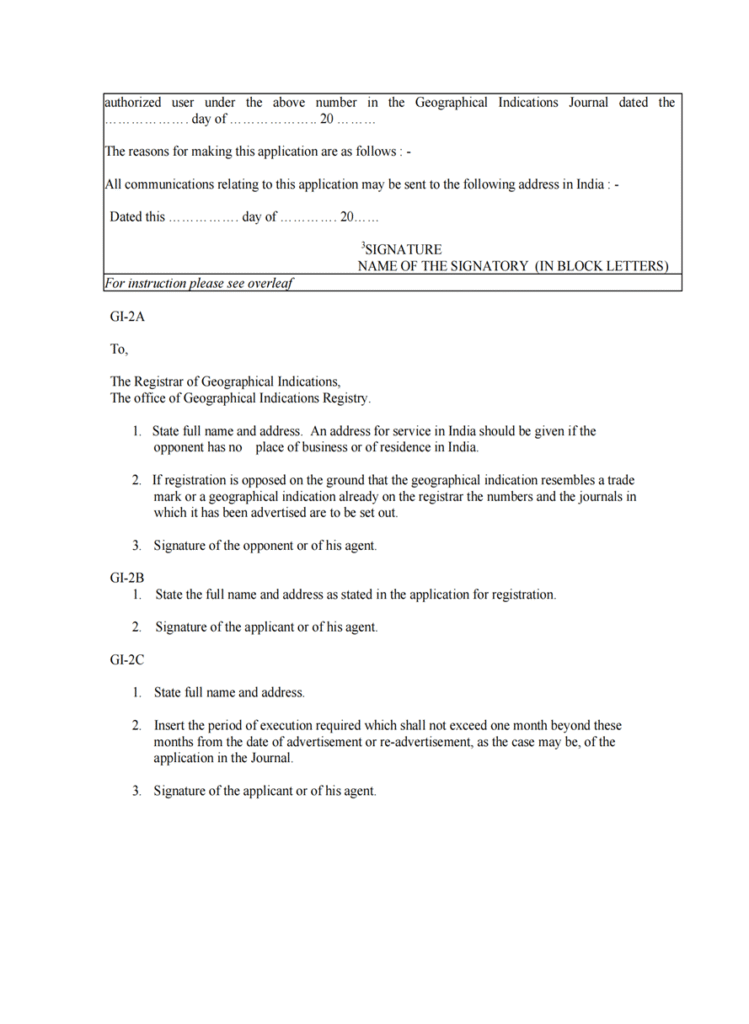

FORM G-1 [63]

[1] LL.M, School Of Legal Studies

[2] Research Scholar, School Of Legal Studies.

[3] Halsbury’s Laws of India (Intellectual Property Rights II, 2nd ed, 2020) para 185.1991

[4] Ibid para 185.1991

[5] Ibid para 185.1987.

[6] Ibid para 185.1989

[7] (Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999)

[8] (Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma v ASDA Stores Ltd, (2002) FSR (3) 37 (HL))

[9] TRIPS Agreement 1994, art 22(1)

[10] (Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999, s 2(1)(g))

[11] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.1991.

[12] Ibid para 185.1991.

[13] Ibid para 185.1991, 185.1993.

[14] Ibid para 185.1993

[15] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) paras 185.1993, 185.1992

[16] Ibid paras 185.2005, 75–76

[17] Payyannur Pavithra Ring, Artisans & Devp v K Balakrishnan 2009 (41) PTC 719 (GIG)

[18] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2004

[19] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2011.

[20] Ibid para 185.2011

[21] Ibid para 185.2020

[22] Ibid para 185.2006.

[23] Ibid para 185.2010

[24] Ibid para 185.2005.

[25] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2021.}.

[26] Ibid para 185.2018

[27] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2026.

[28] Ibid para 185.2027.

[29] Ibid para 185.2027.

[30] Ibid para 185.2029

[31] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2030

[32] Ibid para 185.2032

[33] Ibid para 185.2034

[34] Ibid para 185.2035.

[35] ibid para 185.2036.

[36] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2040

[37] Ibid para 185.2047

[38] Ibid para 185.2058

[39] Ibid para 185.2061

[40] Ibid para 185.2044

[41] Ibid para 185.2045

[42] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) paras 185.2045, 185.2068

[43] Ibid para 185.2049

[44] Ibid para 185.2050

[45] Ibid para 185.2052

[46] Ibid para 185.2056.

[47] Ibid para 185.2054

[48] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) para 185.2055

[49] Ibid para 185.2066

[50] Ibid para 185.2068

[51] Ibid para 185.2068

[52] Ibid para 185.2066

[53] Ibid para 185.2069

[54] Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma v ASDA Stores Ltd (2002) FSR (3) 37 (HL).

[55] Halsbury’s Laws of India (n 1) paras 185.1987, 185.1996

[56] Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999, s 2(1)(k)

[57] Ibid para 185.2004

[58] Ibid para 185.2004

[59] Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999, s 11(2)

[60] Subhash Jewellery v Payyannur Pavithra Ring, Artisans & Devp Society 2013 (15) PTC 197 (IPAB)

[61] Vandana Singh, The Law of Geographical Indications: Rising Above the Horizon (Eastern Law House 2017)

[62] SK Sonam and M Hussain, “Commercialization of Indigenous Health Drinks as Geographical

Indications” (2011) 16 Journal of Intellectual Property Rights 170

[63] Geographical Indications Registry, Form GI–1: Application for the Registration of a Geographical Indication, under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, (Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Govt. of India), available at https://ipindia.gov.in/geographical-indications.htm (last visited Oct. 28, 2025).