Author(s): Damita Rally

Paper Details: Volume 3, Issue 1

Citation: IJLSSS 3(1) 57

Page No: 624 – 632

ABSTRACT

In India, domestic violence—which can take the form of physical, emotional, psychological, or financial harm—remains one of the most prevalent types of abuse against women. An important legislative step toward defending women’s rights in the home was the passage of The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA). With special reference to Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, now Section 84 of Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS) and the procedural framework set up under the PWDVA, this article examines the dual civil and criminal nature of domestic violence under Indian law. It also looks at the crucial role that family courts have played in providing easily accessible, humane, and fair resolutions to family conflicts and cases of domestic abuse since their founding in 1984. Through an examination of statutory provisions, legal precedents, and empirical data, specifically from the National Family Health Survey and the National Crime Records Bureau, the study demonstrates a significant decrease in domestic violence cases following the Act’s implementation. Stronger legal protections, rising public awareness, and more reporting are all factors in this decline. The article’s conclusion highlights the significance of effective legal systems, the growth of infrastructure, and neighbourhood-based programs like Mahila Adalat’s and One Stop Centres, all of which are essential for the long-term protection and empowerment of women in India.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most prevalent types of abuse against women is domestic violence. By definition, it is the use of force, whether physical, psychological, or emotional, done against another individual with the goal of causing injury or gaining authority and control over them. Any person who knows the victim well enough to enter her home and commit an act of domestic violence is a potential offender. For the purposes of defining “domestic violence,” it is not essential that the victim and the offender share the same residence; rather, the term is defined by the proximity of the relationship between the offender and the person who is abused[1]. Although domestic violence is widely acknowledged as a social issue, it is nonetheless shrouded in stigma and taboo. Physical and/or mental abuse is a problem for many women in their closest social circles and marital partnerships.

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005 was made by the Indian Parliament to protect women from violence in the home. Family courts also play an important `role in the cases related to domestic violence.

Section 498A (1983) of the Indian Penal Code says, “Husband or relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty- Whoever, being the husband or the relative of the husband of a woman, subjects such woman to cruelty shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine.”.[2]

When it comes to public health concerns, domestic violence ranks high on the list because of the number of people it impacts and the severity of the harm it may cause, including physical, emotional, financial, and even fatal consequences. However, there are still disagreements over the specifics of the crime. There are still discrepancies over the nature of the wrong committed. No one can agree on whether or not this is a civil offence or a criminal offence.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: A CIVIL OFFENCE OR A CRIMINAL OFFENCE

As of 1983, domestic violence is a punishable or criminal offence in India after the inclusion of section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code. Abuse of a wife by her husband or his relatives is the subject of this section. Then on June 23rd, 2005, Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Bill was approved by cabinet, and subsequently signed into law by both houses of parliament. With this vote, a new civil law on domestic violence has been passed, giving victims of domestic violence access to emergency relief services.

Although the reliefs granted by the court, such as protection, relocation, and monetary orders, are civil in nature, the proceedings are guided by the Criminal Procedure Code or procedure which is determined by the Court pursuant to Section 28 of Domestic Violence Act. Section 26 of Domestic Violence Act allows a victim to file an application with a Civil, Family, or Criminal Court. As a consequence, it’s uncertain whether domestic violence offences are criminal or civil in nature.

According to the high court of judicature in Madras, the rights that are safeguarded and enacted under the Act are deemed to be purely civil in nature but, these proceedings have taken on a criminal hue because of the forum which heard these applications and the method used. The Magistrate’s deliberations have the essence of a civil proceeding when deciding an application under Chapter IV of the Domestic Violence Act, but the essence of a criminal proceeding when trying an offence as per Chapter V of the Act. However, the merging of civil and criminal jurisdictions in the Magistrate does not totally destroy the unique characteristics of either. The true test is not the nature of the Tribunal adjudicating such a proceeding but rather the character of the proceeding itself, which depends on the nature of the right violated and the relief claimed thereon. Even though a Magistrate may be asked to rule on and enforce civil rights in an application filed under Chapter IV of the D.V Act, this does not make the proceeding one of a criminal nature[3].

The Secretary of Department of Women and Child Development said “The existing civil, personal or criminal laws leave certain gaps in addressing the issue of Domestic Violence. Under criminal law, if a husband perpetrates violence on his wife, she may file a complaint under Section-498 A of IPC. Similarly, under the civil law, if there is disharmony in a family and the husband and wife cannot live together, any one of them may file a suit for separation followed by divorce. However, the present Bill addresses such situation where there is some disharmony in the family but the situation has not yet reached a stage where either separation or divorce proceeding has become inevitable and the aggrieved woman also for some reasons does not want to initiate criminal proceedings against her perpetrator. Therefore, the Bill seeks to give the aggrieved woman an alternative avenue whereby she can insulate herself from violence without being deprived of the basic necessities of life and without disintegrating her family.”[4]

In Kunapareddy Case (2016), the Supreme Court decided that the Domestic Violence Act was implemented to give the victims a civil law remedy. It was formulated “In fact, the very purpose of enacting the DV Act was to provide for a remedy which is an amalgamation of civil rights of the complainant. Intention was to protect women against violence of any kind, especially that occurring within the family as the civil law does not address this phenomenon in its entirety. It is treated as an offence under Section 498-A of the Penal Code, 1860. The purpose of enacting the law was to provide a remedy in the civil law for the protection of women from being victims of domestic violence and to prevent the occurrence of domestic violence in the society. It is for this reason, that the scheme of the Act provides that in the first instance, the order that would be passed by the Magistrate, on a complaint by the aggrieved person, would be of a civil nature and if the said order is violated, it assumes the character of criminality.” [5]

Later, in 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in Satish Chander Ahuja Case that Domestic Violence proceedings are criminal in nature and therefore subject to the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) as laid down in Section 28[6] of the Act. It was later established that a judgement cannot be considered a binding precedent under Article 141[7] of the Constitution of India if the nature of the hearing before the Magistrate under Domestic Violence Act was consciously not paid attention to.

Even after fifteen years, important questions regarding its implementation remain. Due to a lack of knowledge about the nature of domestic violence, the courts are not able to come to a consensus on whether domestic violence is a civil or criminal offence; however, the Domestic Violence offences may be seen by the courts as being somewhere in between the two i.e., as quasi-criminal and quasi-civil. Magistrate cannot, however, treat an application under the D.V Act as though it is a complaint case under the CrPC.

A DECLINE IN CRIMES (DOMESTIC VIOLENCE) AGAINST WOMEN IN THE DOMESTIC SPHERE DUE TO THE EXISTENCE OF FAMILY COURTS

Family courts were established in 1984 with the goals of safeguarding the institution of marriage, ensuring the well-being of children, and facilitating the peaceful resolution of legal disputes through mediation.

The trend of domestic violence has been declining steadily over the past few years. A decrease is visible in the rate of domestic violence suffered by the women in their respective domestic environment. The existence of domestic courts plays a vital role as now there is a fear of legal liability among the men.

There were 30,865 formal complaints received in the year 2021. When compared to the 19,730 complaints filed in 2019, 2020 saw a rise to 23,722.[8][9] The fact that these figures are rising shows that the general public is becoming more informed and indicates rising public confidence in the judicial system. The establishment of family courts in India has raised public awareness of a problem that previously went unreported. However, this does not mean that the rate of domestic violence has also seen a rise. Rather this is an indicator of increased awareness and a greater number of cases regarding domestic violence offence being addressed. Even though the complaints against domestic violence are rising, the rate of domestic violence is decreasing. This indicates that women are standing against the social evil of domestic violence and the cases that earlier went unreported were now coming in the judicial light. It also suggests that people have become more aware of their rights.

Since previously unseen cases are now being reported, a rise is observed in the complaints under the same and more victims are receiving justice. The rights of the women are being recognized, and they are able to utilize the rights they are entitled to. The rate of domestic violence is also on a decline. Thus, the aim with which the family courts were established is being fulfilled.

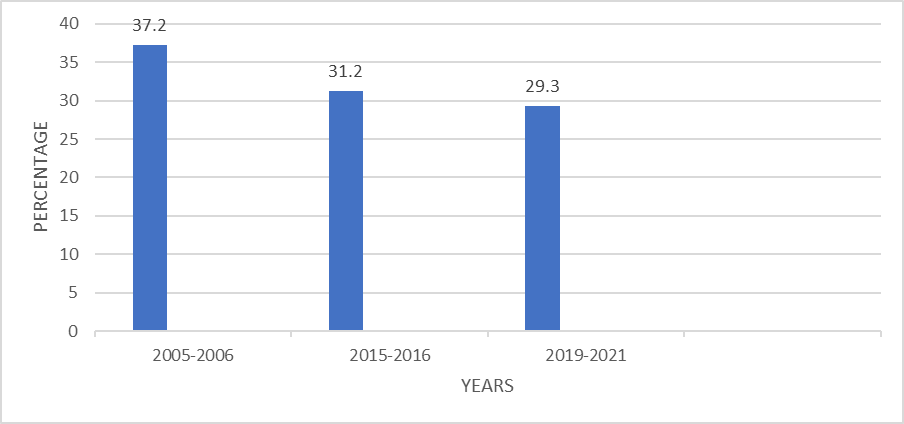

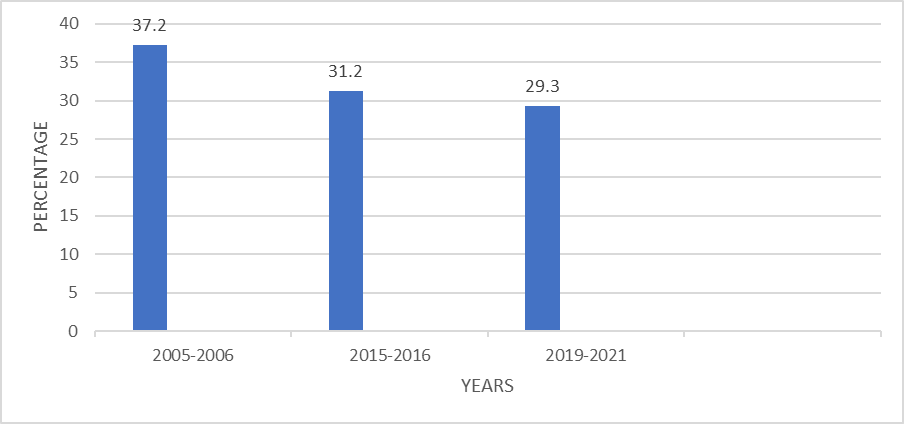

DATA ON DOMESTIC VIOLENCE BY NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH SURVEY (NFHS)

Source: National Family Health Survey (rchiips.org)

A DECLINE IN CRIMES AGAINST WOMEN IN THE DOMESTIC SPHERE AFTER THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT 2005

On October 26, 2006, the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005 (PWDVA) became law.

According to the NFHS report, domestic violence has declined in India after the implementation of domestic violence act of 2005. The percentage has dropped from 37.2 in 2005-06 to 29.3 in 2019-21.[10] According to the crime report of India published by the National Crimes Record Bureau, 507 cases were reported in the year 2021 under the domestic violence act. Furthermore, the report also outlined that 446 cases and 553 cases were reported for the year 2020 and 2019 respectively.[11]

It can therefore be concluded that there is a decline in the number of cases of domestic violence after the implementation of domestic violence act. Even though there is a slight rise in the number of cases in the year 2021, the overall trend is on a decline.

According to the judicial system, domestic violence is both a civil and criminal matter. Violence against women is viewed as one of society’s highest priorities. Family courts have been established, and various provisions, such as the Domestic Violence Act of 2005, have been enacted, as a result. The fact that the number of cases has gone down since family courts

were established, more people are now also aware of the remedies available to them. There has been a significant drop in the incidence of domestic violence in India, which is largely attributable to the passage of the Domestic Violence Act.

The hypothesis of the research conducted stands correct and confirmed as the family courts and passage of Domestic Violence Act are able to induce a positive effect on the situation.

The primary goal of these legal protections and institutional frameworks is to ensure that women’s rights and esteem are maintained. The Protection Officer and service providers were instituted under the law to protect the female victims from harassment in the society and from the stigmas attached to court proceedings. The aid given to the women victims is both empowering and practical. Protection orders, residence orders, orders for monetary relief, compensation and temporary custody are some of the remedies provided to women under the 2005 Act. Aid is provided to women in the form of housing, support, and financial compensation, all of which serve to strengthen their position in society and empower them.

In order to further reduce domestic violence in India and to empower the female victims, effective and efficient implementation of the schemes, acts or institutions is required. According to data submitted by the National Legal Services Authority before the Supreme Court, there are currently 4,71, 684 original cases and 21,088 appeals pending under the Domestic Violence (DV) Act in the country. In order to deliver fair punishment and give victims a voice in the legal process, the judicial system must operate effectively. This can be achieved in two ways: either by incorporating technological solutions into our judicial system or by improving case management practices.

Protection Officers at the district level are typically current government officials. Overburdening is the result of insufficient resources, including training, infrastructure, and support. To solve this issue, we need to establish reliable training facilities and invest in the necessary infrastructure.

As a form of alternative dispute resolution, mahila Adalat (or women’s court) is intended to be a safe space for women to express their grievances, reach agreements with their husbands and in-laws, or move out from abusive relationships. Instead of going to court, it encourages family disputes to be settled amongst the women themselves in an informal way. The government should also promote and educate the public on these forms of dispute resolution.

Policies like ‘One Stop Centre’ for violence affected women should also be launched for women aged above 18 years. The government can do more to help victims regain control by increasing access to services, increasing funding for shelters and other forms of safe housing, and increasing public awareness through public information campaigns.

CONCLUSION

According to the judicial system, domestic violence is both a civil and criminal matter. Violence against women is viewed as one of society’s highest priorities. Family courts have been established, and various provisions, such as the Domestic Violence Act of 2005, have been enacted, as a result. The fact that the number of cases has gone down since family courts were established, more people are now also aware of the remedies available to them. There has been a significant drop in the incidence of domestic violence in India, which is largely attributable to the passage of the Domestic Violence Act.

The primary goal of these legal protections and institutional frameworks is to ensure that women’s rights and esteem are maintained. The Protection Officer and service providers were instituted under the law to protect the female victims from harassment in the society and from the stigmas attached to court proceedings. The aid given to the women victims is both empowering and practical. Protection orders, residence orders, orders for monetary relief, compensation and temporary custody are some of the remedies provided to women under the 2005 Act. Aid is provided to women in the form of housing, support, and financial compensation, all of which serve to strengthen their position in society and empower them.

In order to further reduce domestic violence in India and to empower the female victims, effective and efficient implementation of the schemes, acts or institutions is required. According to data submitted by the National Legal Services Authority before the Supreme Court, there are currently 4,71, 684 original cases and 21,088 appeals pending under the Domestic Violence (DV) Act in the country. In order to deliver fair punishment and give victims a voice in the legal process, the judicial system must operate effectively. This can be achieved in two ways: either by incorporating technological solutions into our judicial system or by improving case management practices. Protection Officers at the district level are typically current government officials. Overburdening is the result of insufficient resources, including training, infrastructure, and support. To solve this issue, we need to establish reliable training facilities and invest in the necessary infrastructure. As a form of alternative dispute resolution, mahila Adalat (or women’s court) is intended to be a safe space for women to express their grievances, reach agreements with their husbands and in-laws, or move out from abusive relationships. Instead of going to court, it encourages family disputes to be settled amongst the women themselves in an informal way.

The government should also promote and educate the public on these forms of dispute resolution. Policies like ‘One Stop Centre’ for violence affected women should also be launched for women aged above 18 years. The government can do more to help victims regain control by increasing access to services, increasing funding for shelters and other forms of safe housing, and increasing public awareness through public information campaigns.

REFERENCES

Anon., 2005. THE PROTECTION OF WOMEN FROM DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT, 2005. s.l.:s.n http://www.ncw.nic.in/sites/default/files/TheProtectionofWomenfromDomesticViolenceAct2005_0.pdf

Anon., 2021. THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS, s.l.: s.n. https://sathyanarayanan.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Crl.O.P.28458-of-2019.pdf

Anon., n.d. National Family Health Survey, India. [Online]. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml

BASU, A., n.d. Legislating on domestic violence. https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/events/2010PGYSem_07article.pdf

M Flury, E. N., 2010. Domestic violence against women: definitions, epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. https://smw.ch/article/doi/smw.2010.13099

Nevagi, A. K. A., 2021. The distinction between 498A and Domestic Violence. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/distinction-between-498a-domestic-violence-advocate-kailash-a-nevagi-1e

Sharma, R. K., 2015. Domestic Violence Act and review of constitutional amendments. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324993949_Domestic_Violence_Act_and_review_of_constitutional_amendments

SRIVATSAV, S. V., 2022. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005- Civil or Criminal?. https://clpr.org.in/blog/the-protection-of-women-from-domestic-violence-act-2005-civil-or-criminal/

[1] What is domestic abuse? (no date) United Nations. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse

[2][498A. Husband or relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty- Whoever, being the husband or the relative of the husband of a woman, subjects such woman to cruelty shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine. Explanation- For the purpose of this section, “cruelty” means—

a) any willful conduct which is of such a nature as is likely to drive the woman to commit suicide or to cause grave injury or danger to life, limb or health (whether mental or physical) of the woman; or

b) harassment of the woman where such harassment is with a view to coercing her or any person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any property or valuable security or is on account of failure by her or any person related to her to meet such demand.]

[3] Venkatesh, N.A.N.A.N.D. (2021) The High Court Of Judicature At Madras. Publication.

[4] Venkatesh, N.A.N.A.N.D. (2021) The High Court Of Judicature At Madras. Publication.

[5] VENKATESH, N.A.N.A.N.D. (2021) THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS. publication.

[6] Procedure- (1) Save as otherwise provided in this Act, all proceedings under sections 12,18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 and offences under section 31 shall be governed by the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974). (2) Nothing in sub-section (1) shall prevent the court from laying down its own procedure for disposal of an application under section 12 or under sub-section (2) of section 23

[7]The law declared by the Supreme Court shall be binding on all courts within the territory of India

[8] Times of India (2021) “Complaints of domestic violence against women spiked in the year of lockdown: NCW Data,” 25 March.

[9] Times of India (2022) “Domestic Violence Plaints to NCW rose to 26% last year,” 17 January.

[10] (no date) National Family Health Survey. Available at: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml.

[11] (no date) National Crime Records Bureau. Available at: https://ncrb.gov.in/en.